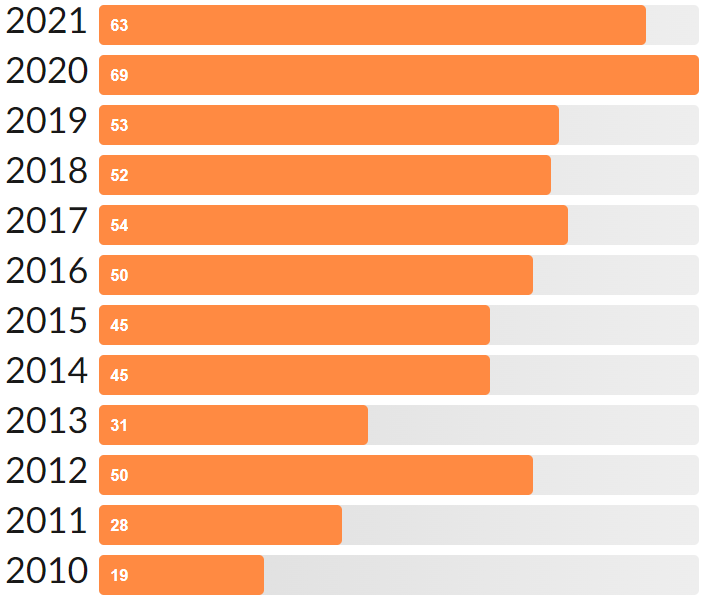

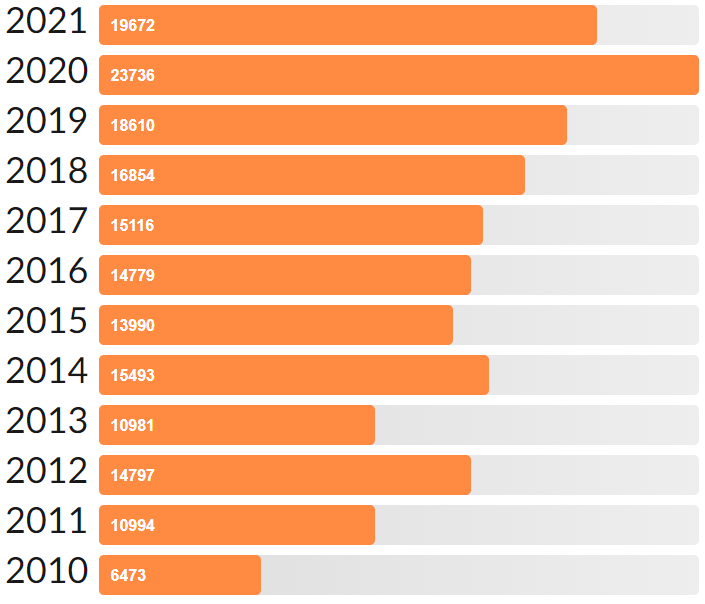

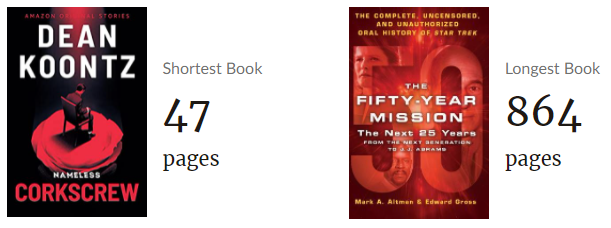

We watch a lot of movies during the Six Weeks of Halloween, but there’s also a fair amount of spooky season’s readings to cover as well. As with this year’s movie watching, our Halloween reading pace has also slackened somewhat from the pandemic-fueled record set last year. I still ended up getting through eight books, which actually isn’t that far off the record, though a couple were shorter and I was still chiseling away at one even after the big day. I used to interweave some book posts throughout the marathon, but we’ll just have to do this one big roundup at the end of the season. We’ve got a lot to get through, so not all will be particularly in-depth analyses, but let’s take a looksee:

The Six Weeks of Halloween: Reading Roundup

Nightmares and Dreamscapes by Stephen King – At this point, it’s almost a cliché to read Stephen King during the Halloween Season, but after reading Night Shift last year, I resolved to explore more of King’s short fiction. As it turns out this was the first book I started and the last book I finished during the season. Short Story collections tend to be, by their very nature, uneven affairs. But when you’ve got a stack of seasonal reads, a book like this makes for the perfect transition between larger works. As such, I was continually dipping into this collection throughout the entire marathon, only finishing it off yesterday (almost a week after Halloween). Clocking in at around 700 pages, that’s not too surprising, I guess, but it was an overall enjoyable read.

“Dolan’s Cadillac” kicks off the collection with a bang and it’s one of the best in the entire collection. More of a horror inflected crime/revenge story than anything else, I appreciated the procedural attention to detail and care with which King constructed the story. “The Night Flier” is a neat little modern (er, for the 80s) spin on vampires, and I very distinctly remember enjoying the movie adaptation that probably won’t live up to my memory (but it’s conspicuously absent from streaming and I’m not willing to spend $65 for a used VHS or DVD to test that theory out). “Home Delivery” is my kinda zombie story. “The Ten O’Clock People” is great, reminiscent of Carpenter’s They Live, but to my mind, better and more horrific (perhaps less pointed or angry in political terms, but creepier in execution for sure). “Crouch End” features the obligatory Lovecraft homage, and is pretty well done iteration of those tropes.

As expected, some stories didn’t really strike a nerve with me (like “The Moving Finger” or “My Pretty Pony”) and one thing I noticed in comparison to Night Shift is that these newer stories all seem longer and more verbose than the earlier ones. When it comes to the good stories mentioned above, that’s not really a problem, but there are a fair amount of stories that I thought were decent but dragged a bit (like “Sneakers” or “You Know They Got a Hell of a Band”). Finally, there are some things that don’t especially fit at all, notably “Head Down”, which is non-fiction about King’s son’s little league baseball team (which, oddly, is also the longest story of the bunch). All in all, though, it’s a pretty solid collection, and while it sags at times, it feels like it got stronger as it went. I will probably continue this trend of a Stephen King short story collection next year, as I kinda enjoy having something to slip in and out of throughout the season.

Winter Moon by Dean Koontz – I know Koontz takes a lot of heat, especially from Stephen King fans, but he’s always been a favorite. That said, he’s extremely repetitive and I’ve never quite managed to rekindle that initial burst of enthusiasm I got from his stuff when I discovered his books in high school. Part of that may be because I’m older and wiser now (haha, right – ed), part of it may be that I’ve already read his best stuff, but most likely it’s that Koontz is very prolific and tends to repeat certain tropes over and over again. That said, there was a period in the 80s and early 90s in which he was really on fire. I’ve actually had some luck earlier this year reading Mr. Murder and The Bad Place, both of which were quite fun (especially the latter, which I found surprisingly entertaining and weird).

Winter Moon was apparently a rewrite of one of Koontz’s earlier works, published under a pseudonym. Supposedly the rewrite used very little of the original text, so it was kinda considered a new novel at the time. Anyway, it’s a fun little alien invasion flick, with the usual sprinkling of Koontzian tropes. Great opening shootout with our police officer protagonist, after which his wife becomes a little paranoid (but not without reason), and the precocious child does his best, etc… Then there’s a parallel story in set in Montana that’s a little more unusual, but you eventually see how the two stories will dovetail. There’s some time spent just kinda waiting for the pieces to fall into place, but it’s easy-going page-turner stuff. Certainly not one of Koontz’s best and not something I’d recommend starting with, but it was entertaining enough.

Wasteland: The Great War and the Origins of Modern Horror by W. Scott Poole – The premise of this nonfiction book is that the devastating violence and bloodshed of World War I planted the seeds of all modern horror. Poole is a historian, so it’s not surprising that a fair proportion of this book is spent chronicling various factual aspects of WWI. He’s good at capturing the outrage and senselessness of the war and even if you’re more interested in the artistic side of this premise, the historical details are still engaging and interesting.

These details are then applied to the emergence of various horror trends of the era, particularly given the prominence and influence of German filmmakers on the genre. He briefly sketches out the lives of several prominent authors and directors, including the likes of F.W. Murnau, Fritz Lang, James Whale, H.P. Lovecraft, Franz Kafka, and several others. Biographical information is relayed in addition to the prominent works of horror they produced.

Unfortunately, it does feel a bit like he’s stretching to make the details fit his thesis, rather than truly developing it. As a result, the book feels narrowly focused, like Poole was only concerned with a small part of what makes a lot of these works great. There’s also not much in the way of tracing this influence far beyond the war. It seems obvious that art produced during the 20s and 30s would be influenced by the war, but how does that influence expand beyond those works through the subsequent decades (even up until today).

None of which is to belittle what the book is doing here. If you’re already interested in the horror stories of the era, it’s a pretty good overview (if you’re not, then it might not hold interest – as mentioned, it doesn’t do much connecting those works to contemporary horror, so there’s not even an in there). I suppose if you were a history buff who never had much interest in the horror genre, it might be eye opening. I liked it well enough, though again, I do feel it was stretching to fit the thesis.

The Final Girl Support Group by Grady Hendrix – I feel like I should like Hendrix’s work more than I do. I really enjoyed the nonfiction Paperbacks from Hell, and We Sold Our Souls was a nice spin on some specific tropes that I found diverting enough (if not amazing or anything). This book, chronicling the travails of real-life final girls as a killer starts picking them off one by one, should really be up my alley.

To be sure, there are a lot of interesting elements here. In the world of this book, all the slasher franchises we know and love from the eighties were based on real stories with real final girls. They have slightly modified names (i.e. our main protagonist is the basis for the Slay Bells series of movies, which are very obviously styled after Silent Night, Deadly Night), but they’re all there. Of course, this sort of exposure comes with its own challenges. There’s a whole seedy and exploitative side to the situation that Hendrix covers aptly. Some of the girls handle it well, others do not. Twenty years later, they’re mostly a group of basket cases. This is perhaps not unrealistic, but it’s also no fun at all. Which I get. The trauma of such events should not be minimized. But you have to make up for that somehow, and Hendrix seems to think having a main protagonist be utterly and completely incompetent is compelling, and it’s not.

I really, really disliked our protagonist. It’s excusable that she did dumb stuff as a teen that wasn’t expecting to be hunted buy a Santa killer. Twenty years later, being paranoid and supposedly prepared, it turns out that she still constantly makes dumb decisions. Perhaps this is more of a “me” thing than the book’s fault, but I really had a hard time rooting for her. The reason we like final girls in horror movies is that they aren’t generally dumb and are capable of fighting back and even defeating the killer. I get that this story is supposed to be more based in realism, but the precept holds: competent protagonists are much more likeable than stupid ones. She even admits, late in the story when she did something tremendously stupid and underestimates a suspect: “I am stupid. I am dumb.” Right, but self-awareness does not inoculate the author from having a stupid protagonist. The worst thing is that she doesn’t need to be incompetent for this story to work. You could make a commentary on how paranoia and preparedness are sometimes not enough and maybe even the price of such precautions is too much… without having to make the character a total dunce.

There’s arguably too much weight on realism in this story, but otherwise, there’s a skeleton of a good plot here. Even some of the realistic stuff represents interesting extrapolations on a world where final girls were real things, and the various explorations of each final girl’s story and the franchises they spawned are great. As mentioned above, though, Hendrix chose perhaps the least likeable of the bunch as his main protagonist – the others all seem much more interesting and active. I listened to the audiobook for this, which probably didn’t help. It’s read by Adrienne King, who was the final girl in the original Friday the 13th. She’s not the worst reader I’ve heard, but it still comes off as more of a stunt than a great choice. I found a lot of things grating about the book, so maybe it’s hard to separate that from the performance, but whatever. I really did not enjoy this book, which is a shame, because it should have been up my alley. One of these days I’ll find a slasher novel that works for me…

Last Days by Brian Evenson – Evenson is my favorite discovery of the year. There’s something of a cult status being built up around him, and after having read a couple books during this Halloween season, I can easily see why. He’s got a simplistic, straightforward style that is deceptively cerebral in nature, and deeply unsettling.

This story of this novel concerns an amputation-obsessed cult that hires a detective (who had his hand chopped off during his last case – and thus is considered trustworthy by the cult) to solve a murder. Naturally, all is not what it seems. What starts as a detective procedural with a Kafka-esque bent, eventually turns (or perhaps curdles) into something more odd and violent than you might expect.

I don’t want to spoil anything, so I won’t spend much more time on it, though I guess that implies the story has more surprises and gotcha twists than it really does. I mean, our detective certainly makes deductions I wasn’t expecting and there are twists, but they’re hard to describe and unlike your usual mysteries. I really enjoyed the weirdness though, and while it’s subtly stylish stuff, it’s still page turning material. Worth seeking out if you’re not scared of strange stuff off the beaten path…

Song for the Unraveling of the World by Brian Evenson – This collection of short stories might be a better place to start than Last Days, but they’re both pretty short books. I found it interesting reading this in contrast to King’s Nightmares and Dreamscapes. Where I found King’s stories to be relatively long (approximately 30 pages with small type/spacing) and verbose, Evenson’s are generally very short (approximately 10 pages, not as densely printed), stripped down, and simple… but no less disturbing.

Stories range from the straightforward horror type, to more adventurous blends of genres, even including a few science fiction tales. You’ve got the obligatory Lovecraft homage (one of the aforementioned SF stories), and there are multiple stories about filmmakers that delve into the horrific.

I liked the initial entries in the book, but either the stories got better as it it went or I simply got on Evenson’s wavelength, because my opinion of this book kept rising as I read (an unusual experience with a short story collection, which is typically more of a wave of ups and downs – I suppose that’s also true here, but the stories are short enough that the amplitude of said waves isn’t that high). If Evenson’s brand of weird and disquieting horror sounds like your thing, check it out. I will most certainly be revisiting his work next year.

Chasing the Boogeyman by Richard Chizmar – A serial killer story with a metafictional twist, this novel is essentially a fictional true crime novel. As such, you don’t get the bombastic serial killer tropes here, only the difficult to reconstruct details of each murder scene and a little about the victim’s life. It’s a fascinating exercise and a premise that mostly delivers what it promises, though I will say that I’m not exactly an expert on true crime.

It did feel more like a memoir than true crime at times, but again, I’m not sure how much of this is a departure from true crime or not (i.e. are a lot of true crime novels also sorta memoirs about the author’s life too?) Either way, the story works well enough for what it is. Again, don’t expect the exciting, pulse-pounding tropes of more trashy serial killer narratives. But it’s not a hollow, overheated stylistic exercise either. It’s a sorta sober examination of a series of murders in the author’s hometown. Unlike a lot of true crime, this one is eventually solved, and the book takes the form of a second edition, with some additional chapters at the end (because the fictional crimes were solved long after the fictional true crime book was fictionally published, so the fictional author was approached by the fictional publisher to revise the fictional book for a fictional second edition – everyone got that?) It works as a story, but also as a metatextual narrative, which is pretty interesting.

Danse Macabre by Stephen King – And so we return to Stephen King, this time working in non-fiction mode as he examines what makes the horror genre tick. Writing in the early 80s, he’s mostly covering older works from his childhood, though he does spend some time on contemporary (i.e. late 70s) horror as well. That part represents an interesting time capsule to see what horror movies resonated at the time, versus the ones that have survived the test of time and are still well known today.

He covers literature and movies, with some time spent on radio and the pulps and whatnot. There’s good overviews of a lot of what makes the genre tick, and he traces things back to originators like Frankenstein, Dracula, and the Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (the latter of which King posits as the origin of modern werewolf stories, which I’m not sure I’d ever heard before).

It’s always interesting to get some perspective on an author like King and how he understands his own work, but I’m guessing there’s a lot to quibble with too. If you’ve ever read King’s column in Entertainment magazine back in the day, well, it’s perhaps not quite that lightweight, but sometimes he strikes off in a direction that seems a bit more flimsy than you might expect. Still, if you’re interested in horror’s evolution through the 50s and 60s, with a little of the 70s, this book will be most interesting for you. Personally, it feels like he might have written it a few years too early – the 80s were an interesting time for horror, and most of that is elided here simply because of when he wrote the book. Hard to blame him for that, so this is definitely another me problem, but the horror heart wants what it wants. I’d recommend King’s On Writing much more than Danse Macabre, but they’re also very different takes on non-fiction, so make of that what you will. King’s always interesting though…

Another Season’s Readings in the books. I’m allready thinking of things I’m going to watch and read for next year’s Six Weeks of Halloween marathon, which is always a good sign…