I mentioned recently that book length is something that’s been bugging me. It seems that we have a somewhat elastic relationship with length when it comes to books. The traditional indicator of book length is, of course, page number… but due to variability in font size, type, spacing, format, media, and margins, the hallowed page number may not be as concrete as we’d like. Ebooks theoretically provide an easier way to maintain a consistent measurement across different books, but it doesn’t look like anyone’s delivered on that promise. So how are we to know the lengths of our books? Fair warning, this post is about to get pretty darn nerdy, so read on at your own peril.

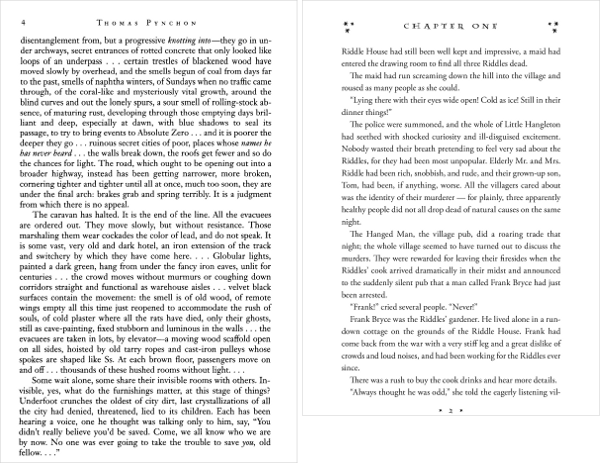

In terms of page numbers, books can vary wildly. Two books with the same amount of pages might be very different in terms of actual length. Let’s take two examples: Gravity’s Rainbow (784 pages) and Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (752 pages). Looking at page number alone, you’d say that Gravity’s Rainbow is only slightly longer than Goblet of Fire. With the help of the magical internets, let’s a closer look at the print inside the books (click image for a bigger version):

As you can see, there is much more text on the page in Gravity’s Rainbow. Harry Potter has a smaller canvas to start with (at least, in terms of height), but larger margins, more line spacing, and I think even a slightly larger font. I don’t believe it would be an exaggeration to say that when you take all this into account, the Harry Potter book is probably less than half the length of Gravity’s Rainbow. I’d estimate it somewhere on the order of 300-350 pages. And that’s even before we get into things like vocabulary and paragraph breaks (which I assume would also serve to inflate Harry Potter’s length.) Now, this is an extreme example, but it illustrates the variability of page numbers.

Ebooks present a potential solution. Because Ebooks have different sized screens and even allow the reader to choose font sizes and other display options, page numbers start to seem irrelevant. So Ebook makers devised what’s called reflowable documents, which adapt their presentation to the output device. For example, Amazon’s Kindle uses an Ebook format that is reflowable. It does not (usually) feature page numbers, instead relying on a percentage indicator and the mysterious “Location” number.

The Location number is meant to be consistent, no matter what formatting options you’re using on your ereader of choice. Sounds great, right? Well, the problem is that the Location number is pretty much just as arbitrary as page numbers. It is, of course, more granular than a page number, so you can easily skip to the exact location on multiple devices, but as for what actually constitutes a single “Location Number”, that is a little more tricky.

In looking around the internets, it seems there is distressingly little information about what constitutes an actual Location. According to this thread on Amazon, someone claims that: “Each location is 128 bytes of data, including formatting and metadata.” This rings true to me, but unfortunately, it also means that the Location number is pretty much meaningless.

The elastic relationship we have with book length is something I’ve always found interesting, but what made me want to write this post was when I wanted to pick a short book to read in early December. I was trying to make my 50 book reading goal, so I wanted something short. In looking through my book queue, I saw Alfred Bester’s classic SF novel The Stars My Destination. It’s one of those books I consistently see at the top of best SF lists, so it’s always been on my radar, and looking at Amazon, I saw that it was only 236 pages long. Score! So I bought the ebook version and fired up my Kindle only to find that in terms of locations, it’s the longest book I have on my Kindle (as of right now, I have 48 books on there). This is when I started looking around at Locations and trying to figure out what they meant. As it turns out, while the Location numbers provide a consistent reference within the book, they’re not at all consistent across books.

I did a quick spot check of 6 books on my Kindle, looking at total Location numbers, total page numbers (resorting to print version when not estimated by Amazon), and file size of the ebook (in KB). I also added a column for Locations per page number and Locations per KB. This is an admittedly small sample, but what I found is that there is little consistency among any of the numbers. The notion of each Location being 128 bytes of data seems useful at first, especially when you consider that the KB information is readily available, but because that includes formatting and metadata, it’s essentially meaningless. And the KB number also includes any media embedded in the book (i.e. illustrations crank up the KB, which distorts any calculations you might want to do with that data).

It turns out that The Stars My Destination will probably end up being relatively short, as the page numbers would imply. There’s a fair amount of formatting within the book (which, by the way, doesn’t look so hot on the Kindle), and doing spot checks of how many Locations I pass when cycling to the next screen, it appears that this particular ebook is going at a rate of about 12 Locations per cycle, while my previous book was going at a rate of around 5 or 6 per cycle. In other words, while the total Locations for The Stars My Destination were nearly twice what they were for my previously read book, I’m also cycling through Locations at double the rate. Meaning that, basically, this is the same length as my previous book.

Various attempts have been made to convert Location numbers to page numbers, with low degrees of success. This is due to the generally elastic nature of a page, combined with the inconsistent size of Locations. For most books, it seems like dividing the Location numbers by anywhere from 12-16 (the linked post posits dividing by 16.69, but the books I checked mostly ranged from 12-16) will get you a somewhat accurate page number count that is marginally consistent with print editions. Of course, for The Stars My Destination, that won’t work at all. For that book, I have to divide by 40.86 to get close to the page number.

Why is this important at all? Well, there’s clearly an issue with ebooks in academia, because citations are so important for that sort of work. Citing a location won’t get readers of a paper anywhere close to a page number in a print edition (whereas, even using differing editions, you can usually track down the quote relatively easily if a page number is referenced). On a personal level, I enjoy reading ebooks, but one of the things I miss is the easy and instinctual notion of figuring out how long a book will take to read just by looking at it. Last year, I was shooting for reading quantity, so I wanted to tackle shorter books (this year, I’m trying not to pay attention to length as much and will be tackling a bunch of large, forbidding tomes, but that’s a topic for another post)… but there really wasn’t an easily accessible way to gauge the length. As we’ve discovered, both page numbers and Location numbers are inconsistent. In general, the larger the number, the longer the book, but as we’ve seen, that can be misleading in certain edge cases.

So what is the solution here? Well, we’ve managed to work with variable page numbers for thousands of years, so maybe no solution is really needed. A lot of newer ebooks even contain page numbers (despite the variation in display), so if we can find a way to make that more consistent, that might help make things a little better. But the ultimate solution would be to use something like Word Count. That’s a number that might not be useful in the midst of reading a book, but if you’re really looking to determine the actual length of the book, Word Count appears to be the best available measurement. It would also be quite easily calculated for ebooks. Is it perfect? Probably not, but it’s better than page numbers or location numbers.

In the end, I enjoy using my Kindle to read books, but I wish they’d get on the ball with this sort of stuff. If you’re still reading this (Kudos to you) and want to read some more babbling about ebooks and where I think they should be going, check out my initial thoughts and my ideas for additional metadata and the gamification of reading. The notion of ereaders really does open up a whole new world of possibilities… it’s a shame that Amazon and other ereader companies keep their platforms so locked down and uninteresting. Of course, reading is its own reward, but I really feel like there’s a lot more we can be doing with our ereader software and hardware.

As a side note, I recently had my own thoughts about page count, along different lines. I tend heavily toward paper-brick space opera, such as Peter F. Hamilton’s Commonwealth and Confederation series. However (thanks to e-readers) I recently began exploring Asimov and Clarke, both of whom I had only a passing and referential familiarity. It struck me that Asimov created in the Foundation novels every bit (mostly) the complex universe as Hamilton, but which many fewer words. Certainly some of the *detail* is missing, but the construction is such that you can easily fill in the gaps with your own imagination.

I’m not sure whether to consider this a function of quality, as such…but I’m not entirely sure the phenomenon is purely the product of style, either.

Last year, I was all about the short SF reads, but I’m trying to remove that impulse this year, and I’ve got some Peter Hamilton paper-bricks in the queue, so we’ll see how that goes.

Golden age SF authors like Asimov and Clarke (and Heinlein) were great at what you’re describing. They were perhaps a bit stilted and prosaic in terms of style, but they had great ideas and were masters of implying complexity through the use of terminology. For instance, “Groundcar” has an obvious meaning, but the fact that Asimov had to modify “Car” with “ground” means that there are probably lots of other types of cars (presumably aircars) in the world he’s depicting. And that also implies a lot of other social and economic things about his world too, if you think about it (i.e. with commonplace aircars, some previously inaccessible areas become easily accessible, etc…). They were really good that that.

But I do think modern authors have a requirement for more literary prose than the golden age authors did. It’s not enough to just have interesting ideas, you need to write in a fashion that’s a little more interesting than just “functional” (which I think is how I’d best describe Asimov and Clarke, at least)…

Regarding functional vs. literary, it was interesting to note the differences from Asimov’s earliest Robot and Foundation stories to the later novels that finished the series. The final four books (all written in the early ’80s, if I remember correctly) covered the same amount of ground as the earlier books but tended to be twice as long. I didn’t pay strict attention, but it does seem that more thought and care were given to the characters themselves in the later books. As interesting overall as Elijah Bailey is, he comes off as a dry cypher with some small grasp on imagination, until the final novel (written much later) in which his characterization finally blooms.

That’s an interesting point too. I haven’t read those books in almost two decades at this point, so I can’t really say for sure, but I do remember the third and four Robot books being a lot longer and slower than the previous two. Being a 15 year old, the notion of literary vs functional didn’t really occur to me, but on the other hand, Prelude to Foundation was really easy to read and long too. I wonder how well that one would hold up today. It always seems to get lost in the classicness of the original Foundation trilogy (and Robot books), but it was my favorite part of when Asimov connected Robots and Foundation…