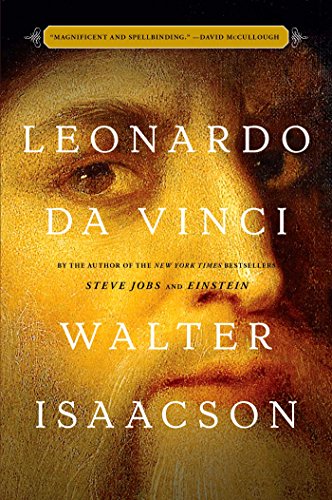

One of the more interesting books I’ve read during lockdown was Walter Isaacson’s biography of Leonardo Da Vinci. I have always done a good job keeping up with reviews of fiction (particularly science fiction), but I’m awful at following up on non-fiction. This despite non-fiction often covering more interesting ideas in more relevant, concrete ways. We’ll try to do Da Vinci justice here.

First up is probably the most significant takeaway from the book:

While at Windsor Castle looking at the swirling power of the “Deluge Drawings” that he made near the end of his life, I asked the curator, Martin Clayton, whether he thought Leonardo had done them as works of art or of science. Even as I spoke, I realized it was a dumb question. “I do not think that Leonardo would have made that distinction,” he replied.

Page 2

It’s worth noting that the notion of art has changed so dramatically since Da Vinci’s time that a lot of what he dealt with seems completely foreign today. His specific brand of naturalism is surely still a thing today, it’s just that it’s a much smaller proportion of art. This insight, that Da Vinci didn’t make a distinction between art and science, is one that recurs throughout the book. Take this:

…Leonardo’s injunction to begin any investigation by going to the source: “He who can go to the fountain does not go to the water-jar.”

Page 6

In these days of “out of context” journalism, going to the original source is as wise a piece of advice as ever. Over and over again, the need for immediate reporting and the bias of journalists lead us down false paths. Even once enough time has passed to figure out what really happened, the damage is done. No one reads the corrections.

Leonardo was human. The acuteness of his observational skill was not some superpower he possessed. Instead, it was a product of his own effort. That’s important, because it means that we can, if we wish, not just marvel at him but try to learn from him by pushing ourselves to look at things more curiously and intensely.

In his notebook, he described his method – almost like a trick – for closely observing a scene or object: look carefully and separately at each detail. He compared it to looking at the page of a book, which is meaningless when taken in as a whole and instead needs to be looked at word by word. Deep observation must be done in steps: “If you wish to have a sound knowledge of the forms of objects, begin with the details of them, and do not go on to the second step until you have the first well fixed in memory.”

Page 179

Another lesson we’d do well to learn. These days, everyone wants to be an immediate expert. No one wants to put in the time to actually become the expert, they just jump to what is considered “the best” and avoid everything else. Something important is lost in the process. I’m reminded of the computer scientist Peter Norvig. Frustrated by the proliferation of books with titles like “Learn Java in 24 Hours”, he wrote a book called Teach Yourself Programming in Ten Years. I think Da Vinci had a similar approach.

He was constantly peppering acquaintances with the type of questions we should all learn to pose more often. “Ask Benedetto Portinari how they walk on ice in Flanders,” reads one memorable and vivid entry on a to-do list. Over the years there were scores of others: “Ask Maestro Antonio how mortars are positioned on the bastions by day or night… Find a master of hydraulics and get him to tell you how to repair a lock, canal and mill in the Lombard manner… Ask Maestro Giovannino how the tower of Ferrara is walled without loopholes.”

Thus Leonardo became a disciple of both experience and received wisdom. More important, he came to see that the progress of science came from a dialogue between the two. That in turn helped him realize that knowledge also came from a related dialogue: that between experiment and theory.

Page 173

More lessons to learn from Leonardo, and the notion that experience and theory are both worth pursuing is an excellent one.

Leonardo… was interested in a part-by-part analysis of the transfer of motion. Rendering each of the moving parts-ratchets, springs, gears, levers, axles, and so on- was a method to help him understand their functions and engineering principles. He used drawing as a tool for thinking. He experimented on paper and evaluated concepts by visualizing them.

Page 190

His drawings served as visual thought experiments. By rendering the mechanisms in his notebooks rather than actually constructing them, he could envision how they would work and assess whether they would achieve perpetual motion. He eventually concluded, after looking at many different methods, that none of them would. In reasoning so, he showed that, as we go through life, there is a value in trying to do such tasks as designing a perpetual-motion machine: there are some problems that we will never be able to solve, and it’s useful to understand why.

Page 196

I like the concept of “drawing as a tool for thinking”, and I see this a lot in my day job. Not only does visualizing something help with understanding it, but it makes a huge difference in communicating it out to others. One example of this sort of thing, I’d been reporting on the benefits of an effort for a couple of months. I had stated one benefit in a text bullet point, but was able to get some actual data and changed it to a graph showing a before and after. I’d been reporting the exact same information for 2 months, but no one really noticed it until I made the graph.

It’s also interesting that Leonardo found value in unsolvable tasks like perpetual motion. Again, it speaks to the expertise problem mentioned above. People want to become immediate experts, but are unwilling to approach anything if it means they might fail. Many of the outlandish things that Leonardo speculated about did come to pass, eventually:

This inability to ground his fantasies in reality has generally been regarded as one of Leonardo’s major failings. Yet in order to be a true visionary, one has to be willing to overreach and to fail some of the time. Innovation requires a reality distortion field. The things he envisioned for the future often came to pass, even if it took a few centuries. Scuba gear, flying machines, and helicopters now exist. Suction pumps now drain swamps. Along the rout of the canal that Leonardo drew there is now a major highway. Sometimes fantasies are paths to reality.

Page 354

Of course, not all of these speculations had as much of an impact as they should:

These laws of friction, and in particular the realization that friction is independent of the contact surface area, were an important discovery, but Leonardo never published them. They had to be rediscovered almost two hundred years later by the French scientific instrument maker Guillaume Amontons. … He also devised ways to use ball bearings and roller bearings, techniques that were not commonly used until the 1800s.

Page 197

He was mainly motivated by his own curiosity. … He was more interested in pursuing knowledge than in publishing it. And even though he was collegial in his life and work, he made little effort to share his findings.

This is true for all of his studies, not just his work on anatomy. The trove of treatises that he left unpublished testifies to the unusual nature of what motivated him. He wanted to accumulate knowledge for its own sake, and for his own personal joy, rather than out of a desire to make a public name for himself as a scholar or to be part of the progress of history. … As the Leonardo scholar Charles Hope has pointed out, “He had no real understanding of the way in which the growth of knowledge was a cumulative and collaborative process.” Although he would occasionally let visitors glimpse his work, he did not seem to realize or care that the importance of research comes from its dissemination.

Page 423

Here we find yet another lesson from Da Vinci. This time, though, it’s something he was bad at that can guide us. He was ahead of his time on many things and made important discoveries… but he never published them, so they had to be rediscovered later. Sometimes for hundreds of years. I suppose this could be seen as a consequence of his ravenous curiosity. He had so much on his mind at all times that he rarely finished any one thing. But he made tons of interesting observations. Some are seemingly trivial and weird, but when we dig deeper, we find something more:

Then comes my favorite item on any Leonardo list: “Describe the tongue of the woodpecker.” This is not just a random entry. He mentioned the woodpecker’s tongue again on a later page, where he described and drew the human tongue. “Make the motions of the woodpecker,” he wrote. When I first saw his entry about the woodpecker, I regarded it, as most scholars have, as an entertaining oddity – an amuse-bouche, so to speak – evidence of the eccentric nature of Leonardo’s relentless curiosity. That it indeed is. But there is more, as I discovered after pushing myself to be more like Leonardo and drill down into random curiosities. Leonardo, I realized, had become fascinated by the muscles of the tongue. All the other muscles he studied acted by pulling rather than pushing a pody part, but the tongue seemed to be an exception. This was true in humans as in other animals. The most notable example is the tongue of the woodpecker. Nobody had drawn or fully written about it before, but Leonardo with his acute ability to observe objects in motion knew that there was something to be learned from it.

On the same list, Leonardo instructed himself to describe “the jaw of the crocodile.” Once again, if we follow his curiosity, rather than merely be amused by it, we can see that he was on to an important topic. A crocodile, unlike any mammal, has a second jaw joint, which spreads out force when it snaps shut its mouth. That gives the crocodile the most forceful bite of any animal.

Page 398

His notebooks feature tons of inventions and concepts that would not be rediscovered for centuries. Just conceiving the idea was often enough for him… but then, that’s a complicated process as well:

When Leonardo drew his Vitruvian Man, he had a lot of inter-related ideas dancing in his imagination. These included the mathematical challenge of squaring the circle, the analogy between the microcosm of man and the macrocosm of earth, the human proportions to be found through anatomical studies, the geometry of squares and circles in church architecture, the transformation of geometric shapes, and a concept combining math and art that was known as “the golden ratio” or “divine proportion.”

He developed his thoughts about these topics not just from his own experience and reading; they were formulated also through conversations with friends and colleagues. Conceiving ideas was for Leonardo, as it has been throughout history for most other cross-disciplinary thinkers, a collaborative endeavor. Unlike Michaelangelo and some other anguished artists, Leonardo enjoyed being surrounded by friends, companions, students, assistants, fellow courtiers, and thinkers. In his notebooks we find scores of people with whom he wanted to discuss ideas.

This process of bouncing around thoughts and jointly formulating ideas was facilitated by hanging around a Renaissance court like the one in Milan.

… Ideas are often generated in physical gathering places where people with diverse interests encounter one another serendipitously. That is why Steve Jobs liked his buildings to have a central atrium and why the young Benjamin Franklin founded a club where the most interesting people of Philadelphia would gather every Friday. At the court of Ludovico Sforza, Leonardo found friends who could spark new ideas by rubbing together their diverse passions.

Pages 158-159

The funny thing about Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man? It also wasn’t really published formally, it’s just a sketch in his notebook. And yet it’s one of the most famous pieces of art ever conceived. And it was a sorta collaboration, or perhaps competition would be more accurate. These days, when someone says Vitruvian Man, we immediately attribute it to Leonardo, but it’s actually a general idea that many artists tackled.

Given Leonardo’s tendency towards collaboration, I have to wonder how many things resulted that we have no idea were inspired by him. As it turns out, attribution is a particularly thorny topic for artists of this time period. They didn’t sign their paintings, so things get very complicated:

There is enough evidence, I think, to support an attribution, in whole or in part, to Leonardo: the use of a walnut panel similar in grain to that of Lady with an Ermine , the existence of some court sonnets that seem to refer to his painting such a work, and the fact that some aspects of the painting have a beauty worthy of the master. Perhaps it was a collaborative work of his studio, produced to fulfill a ducal commission, with some involvement from Leonardo’s brush but not his heart and soul.

Page 248

What is most interesting about the portrait is Silverman’s quest to prove that it was by Leonardo. Like most artists of his time, Leonardo never signed his works nor kept a record of them. So the question of authentication – figuring out which truly deserve to be called autograph works by Leonardo – becomes yet another fascinating aspect of grappling with his genius. In the case of the portrait that Silverman bought, the saga involved a combination of detective work, technical wizardry, historical research, and connoisseurship. The interdisciplinary effort, which wove together art and science, was worthy of Leonardo, who would have appreciated the interplay between those who love the humanities and those who love technology.

Page 250

One of the veils blurring our knowledge of Leonardo is the mystery surrounding the authenticity and dates of some of his paintings, including ones we think are lost and others we think are finds. Like most artist-craftsmen of his era, he did not sign his work. Although he copiously documented trivial items in his notebooks, including the amount he spent on food and on Salai’s clothes, he did not record what he was painting, what he had completed, and where his works went. For some paintings we have detailed contracts and disputes to inform us; for others we have to rely on a snippet from the sometimes reliable Vasari or other early chronicles.

Page 325

… we need to look at copies done by his followers to envision works now lost, such as the Battle of Anghiari, and to analyze what were thought to be works by his followers to see if they might actually be autograph Leonardos. These endeavors can be frustrating, but even when they do not produce certainty, they can lead to a better understanding of Leonardo, as we saw in the case of La Bella Principessa.

Page 325

In 2011 a newly rediscovered painting by Leonardo surprised the art world. Each decade, a dozen or so pieces are proposed or pushed as having a reasonable claim to be previously unknown Leonardos, but only twice before in modern times had such assertions ended up generally accepted

Page 329

One of the striking things about Da Vinci is just how little work is actually attributed to him. And yet, two of his paintings (The Mona Lisa and The Last Supper) are arguably the most famous paintings ever made. There is, of course, lots more of interest in the book, but I’ll leave you with a concept that he invented, called Sfumato:

The term sfumato derives from the Italian word for “smoke,” or more precisely the dissipation and gradual vanishing of smoke into the air. “Your shadows and lights should be blended without lines or borders in the manner of smoke losing itself in the air,” he wrote in a series of maxims for young painters. From the eyes of his angel in Baptism of Christ to the smile of the Mona Lisa, the blurred and smoke-veiled edges allow a role for our own imagination. With no sharp lines, enigmatic glances and smiles can flicker mysteriously.

Page 41

Sfumato is not merely a technique for modeling reality more accurately in a painting. It is an analogy for the blurry distinction between the known and the mysterious, one of the core themes of Leonardo’s life. Just as he blurred the boundaries between art and science, he did so to the boundaries between reality and fantasy, between experience an mystery, between objects and their surroundings.

Page 270