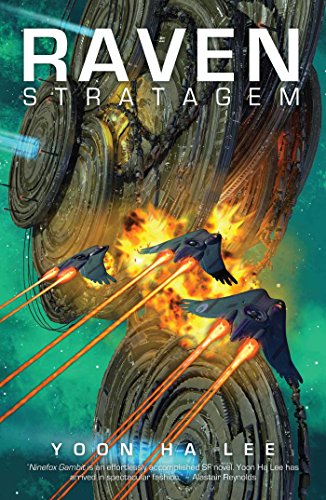

Hugo Awards: Raven Stratagem

Yoon Ha Lee’s Ninefox Gambit was a dense, sometimes gruesome Space Opera. I really enjoyed it, and it was nominated for a Hugo Award last year. Raven Stratagem is the follow up, second in a trilogy, and yes, I enjoyed this one too, despite it succumbing to traditional middle entry in a trilogy syndrome.

I was initially a little hesitant to pick up this sequel. As much as I enjoyed it, I remember the first novel being a bit difficult to follow at parts, and I didn’t entirely remember what had happened (I read it almost two years ago) except in broad strokes. Fortunately, Raven Stratagem presents itself in a much more accessible manner than its predecessor, which allows you to ease back into the universe without too much strain.

We continue to follow the bleshed personalities of Kel Cheris and Shuos Jedao, quasi-successful at retaking the Fortress of Shattered Needles in the first book, as they now set out to defend the Hexarchate from an invading enemy, the Hafn. Cheris is a gifted mathematician and infantry captain for the subservient Kel faction. She’s been possessed by the “ghost” of long-dead military genius, madman, and mass murderer, Jedao, of the Machiavellian Shuos faction. The Hexarchate being an oppressive tyrannical semi-dystopia, the leaders/dictator aren’t sure if they can trust Jedao and his stated intention to simply repel the Hafn. For that matter, neither is the fleet that Jedao has taken over for that purpose. General Kel Khiruev even attempts to assassinate Jedao, but eventually succumbs to Jedao’s, er, charms? That’s not the quite the right word, but it gets the job done, I guess.

So yeah, that brief description kinda captures the density of the worldbuilding, but again, Raven Stratagem is more accessible at laying this out than Ninefox Gambit. This is a best-of-both-worlds situation here. I appreciate dense worldbuilding, and Lee was able to make it more approachable without losing anything. Shuos Jedao, despite frequent reminders of atrocities he’s committed in the past, remains a fascinating character and indeed, things tend to bog down a bit whenever we’re not following him (and I should add her, as Cheris is a woman). I found myself much less interested in the Hexarchate politics side of the story, which comprises a large portion of the second act, though it’s clearly a necessary part of the story.

There are some twists and turns along the way. One of them, which I think is played as a twist, was actually something that I thought I had just misremembered from the first book, but which it turns out, I remembered correctly*. But the final revelation sets up a genuinely interesting premise for the third book to tackle. Unfortunately, that leaves this book in a sorta limbo, as a lot of middle entries in a series feel. This is excellent, but it’s not self-contained, and that always makes Hugo voting a little tricky. Of course, the Hugo context is a bit unfair – as middle entries go, this is a good one, and it moves the story along briskly (which is more than can be said about a lot of middle novels). In any case, Lee’s worldbuilding is solid, but quite dark and sometimes gruesome. Fortunately, he doesn’t wallow in the misery in the way that other books tackling similar themes seem to do.

As Science Fiction, I’m not entirely sure the whole Calendrical Math thing feels grounded enough; it feels more like a metaphorical representation of the way the Hexarchate is controlled than an actual mathematical thing. That not a terrible thing, and it does seem to be played with an internal consistency that I appreciate. Again, Cheris and Jedao are interesting, and their immediate surroundings work, but as mentioned above, once you get beyond that, the story falters a bit.

This is a good book, and Lee’s skill is worth rewarding with a Hugo Award, but I don’t think this is the book to do it. As the second in a series, it feels incomplete (again, not in a way that is bad outside of the Hugo context), which makes it difficult to judge against other books. On the other hand, I expect this will actually do well when it comes time to put in my ballot – I like this work, so I suspect it will come out ahead of several other nominees that I’m unsure about. Fortunately, Lee also has a novelette that’s been nominated, Extracurricular Activities, which is self-contained and excellent. It follows Jedao back when he was a young officer, and bears a sorta Bujold-esque feel to it, which I naturally love (this is high praise, people). I haven’t read any of the other novelette finalists, but I suspect this one will top my ballot. Ultimately, I will most likely pick up the final book in this trilogy, which says a lot, and I greatly look forward to whatever Lee tackles next.

* (Spoilers) I had assumed that Jedao’s ghost had died in the betrayal at the end of Ninefox Gambit, but for most of this book, Cheris is basically just pretending to be Jedao, and since she still has all of his memories implanted in her consciousness, she can pull it off. Lee can get away with this because we mostly see Jedao from the perspective of others, like Khiruev, and Cheris has no reason to let on that she is using Jedao’s reputation for her own purposes (which, to be fair, were also Jedao’s).