Revisiting Snow Crash

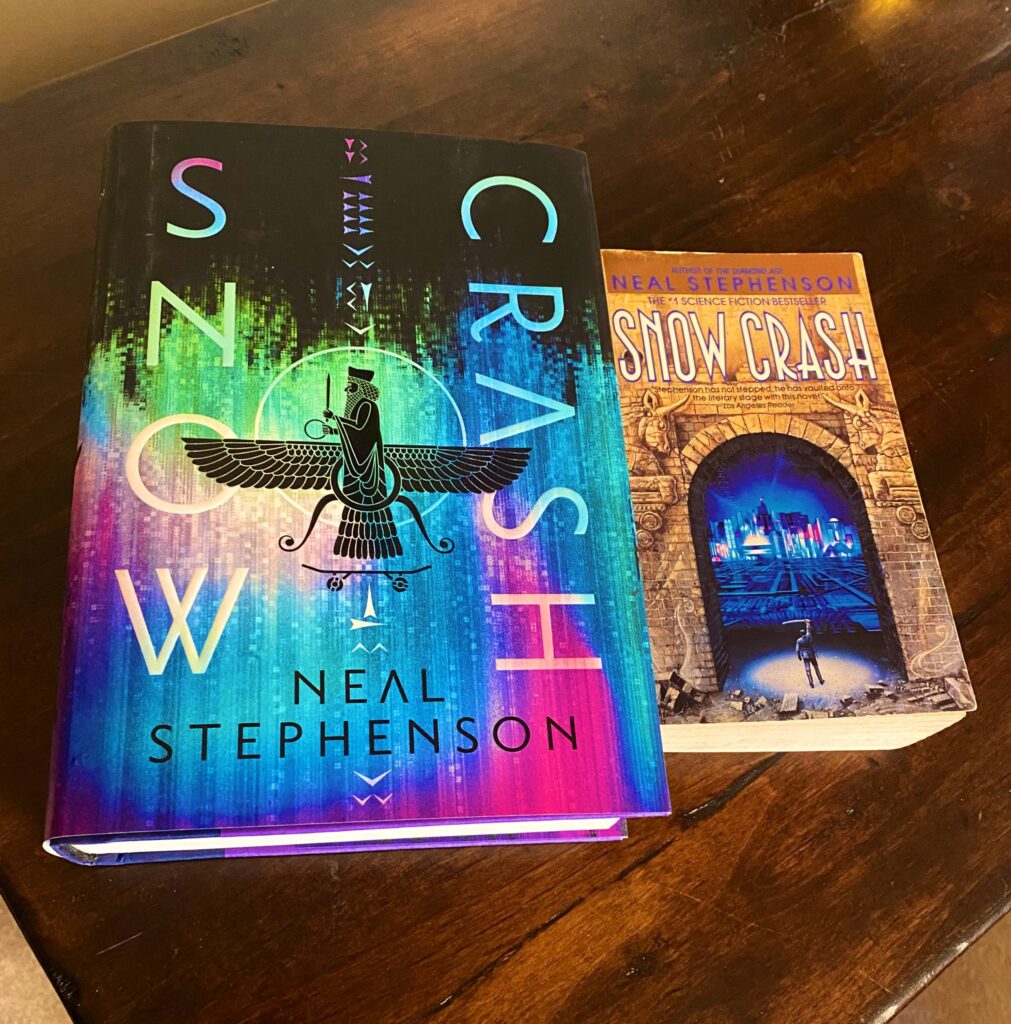

I bought the paperback edition of Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash sometime around 1993-1994. Near as I can tell, this was the first edition of the mass market paperback (Bantam paperback edition / May 1993). Obviously, I enjoyed it quite a bit at the time, and it’s become one of the few books I’ve reread multiple times. As a book of dense ideas, it’s natural that new things strike me with each subsequent reread. People like to dismiss rereading/rewatching because the book hasn’t changed, but that doesn’t take into account that you’ve changed (and the world has changed… not to mention that the book actually might have been changed without notice for dubious reasons).

My first read of Snow Crash struck me as a fun Science Fiction action story about a samurai sword-wielding pizza delivery boy saving the world from a computer virus that originated in Sumerian myth. Lots of interesting ideas and weird tonal stuff went over my head. Subsequent rereadings happened after I’d sampled more of the cyberpunk canon (thus better recognizing the more parodic elements of Snow Crash for what they were) and learned more about linquistics and so on, all of which gave the book enough new context that it felt fresh. Such is the power of a dense book of ideas.

Anyway, 2022 was the 30th anniversary of Snow Crash, and seeing as though my paperback was basically falling apart, I splurged on a new anniversary edition of the book, complete with new, “never-seen-before material” and pages that aren’t falling out of the book. It’s been approximately a decade since I’d last reread it, and a few things struck me about it.

It’s always been hailed as a sorta prescient book, for obvious reasons. Stephenson was clearly ahead of the curve when it came to the internet, computers, and hacking, not to mention popularizing the notion of “avatars” and other stuff like VR and AR and so on. But the thing that struck me this time around was that the Metaverse, as portrayed in the book, is essentially a social network, and Stephenson clearly saw the potential drawbacks. Early in the book, our Hiro Protagonist meets up with an old friend named Juanita. In the world of the novel, they both worked on the early Metaverse infrastructure, but Juanita had pulled back somewhat of late, because:

… she has also decided that the whole thing is bogus. That no matter how good it is, the Metaverse is distorting the way people talk to each other, and she wants no such distortion in her relationships.

Snow Crash, Page 74

It’s a perfectly concise and trenchant critique of social networks (that is implicitly elaborated on throughout the book). I mean, it’s not like we haven’t all been drowning in this realization for the past decade, but it’s always good to remind ourselves that we saw it coming a few decades ago… and yet, still fall into the trap all the time.

It’s also worth noting that people have been trying (and failing) to implement the virtual reality Metaverse since the book came out. Right now, Mark Zuckerberg is literally dumping billions into his conception of the Metaverse… and no one is biting. It’s funny to read, though, that even Stephenson recognized the limitations of the VR approach:

And when hackers are hacking, they don’t mess around with the superficial world of Metaverses and avatars. They descend below this surface layer and into the netherworld of code and tangled nam-shubs that supports it, where everything that you see in the metaverse, no matter how lifelike and beautiful and three-dimensional, reduces to a simple text file: a series of letters on an electronic page.

Snow Crash, Page 401

I have not really played around with VR much, but the notion of bulky goggles is enough to make me think it won’t find much of a mass audience until we get less obtrusive methods of connecting and viewing a VR space. And, like, they have their own drawbacks. The notion of plugging something directly into your eyeballs or jacking the eye’s connection to the brain somehow seems… inadvisable. I dunno, maybe contact lenses might work?

So not everything has aged quite as well (there’s a whole subplot about an infection that is spread through vaccines, which is a conspiracy theory that is obviously a more touchy subject these days). Anywho, it’s still a great book, and worth revisiting if you haven’t read it in a while. The “never-seen-before material” at the end of the book comes in screenplay form, and provides a bit of background for the character of Lagos, who people mostly just talk about in the rest of the novel. It’s a nice treat for Stephenson obsessives like myself, but mostly unnecessary.