Airborne Ranger

THE ELITE UNIT has always captured the imagination of both soldier and

civilian. Units such as the Rangers are the point men of the armed

forces, the cutting edge, and they fascinate us to an extent out of

proportion to their numbers. We envy them their sharp, distinctive

appearance, their high status, their esprit de corps. and most of all

their awesome skill in their chosen profession. They have an aura of

competence that is at once reassuring and intimidating, as if they

will admit no limits to what they can achieve. This unshakeable

confidence would seem preposterous if it had not been borne out time

and again by events on and off the battlefield. The really are as good

as they think they are.

– An excerpt from Airborne Ranger Field Manual

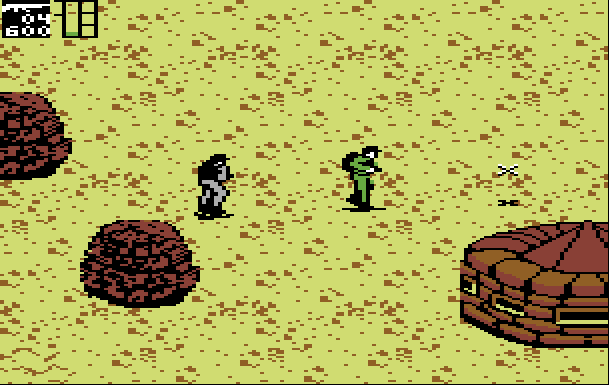

My favorite game for the Commodore 64 was a 1987 military simulation called Airborne Ranger. I don’t consider myself an expert in video games of the era, but I believe this is among the first military themed-games that valued stealth and tactical planning, paving the way for venerable successors like Operation Flashpoint, Metal Gear Solid, and Rainbow Six (and all the other Tom Clancy games). Quite frankly, I think I’d rather play more Airborne Ranger than Rainbow Six, which says something about this game. If it weren’t for the poor emulator support and controls, I’d probably still play this game all the time.

The game consisted of several missions in which a lone Airborne Ranger, controlled by yourself, infiltrated enemy territory and carried out various tasks like stealing a code book, destroying a munitions depot, knocking out an enemy radar array, and freeing hostages (amongst other such tasks). As you complete tasks, your ranger is promoted, eventually attaining the rank of Colonel. As previously mentioned, some missions require stealth (in one, you have to steal an enemy uniform to infiltrate the target area) and almost all warrant careful planning. While each mission has required objectives, how you carry out your mission is left up to you. You’re given a limited amount of ammunition (some of which can get lost during the air drop if you’re not careful), so even when stealth is not required, you must choose your targets carefully. If you run out of ammo, your ranger is captured, but when that happens, other rangers in the roster have a new rescue mission available to them (and if you’re successful, you can continue playing with your original character). This is a good thing, because once your character dies, he’s dead and you can’t use him anymore. Of course, you can run practice missions to make sure you’ve got the hang of a level, but the maps and objective locations are generated randomly each time you play the mission, so there’s no guarantee (this also requires you to think quickly during a mission, as you won’t know what you’re up against until you actually start the mission).

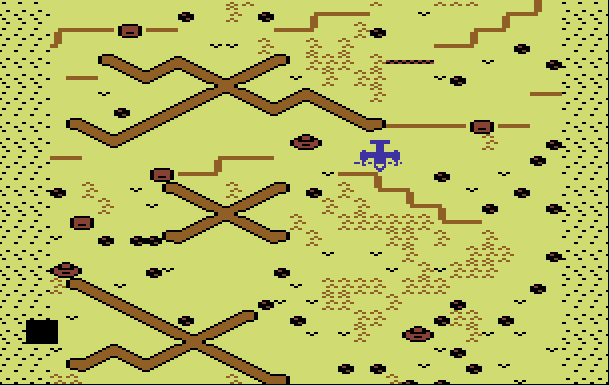

After choosing a mission, you are briefed and then given control of an aircraft. As it flies over the enemy territory, you have a chance to drop 3 duffel bags filled with supplies (ammo, medical kits, etc…) You need to be careful where you drop these supplies though – if one of the bags hits a tree, barbed wire or other obstacle, those supplies are lost.

As you get towards the bottom of the map, the drop light comes on and you parachute to the surface. This is where the bulk of the game takes place. At this point, you need to carefully make your way up the map, gathering the supplies you dropped and avoiding enemy forces (or not, depending on the mission), until you reach your objective. Once your mission is complete, you need to high-tail it to the extraction point and hold off the enemy until your ride shows up…

The game is lots of fun, and it holds up reasonably well even today. Sure, the graphics and sound are horrible by today’s standards, but the concept is well designed and executed. It’s probably comparable to the NES games of the era in terms of graphics and sound, but the gameplay is great (incidentally, there are several other versions of the game for other platforms, including the higher-end Commodore Amiga, which had much better graphics). You play the game frome a pseudo-3D perspective that was somewhat rare at the time and commonplace today (it’s similar to the Metal Gear Solid and Grand Theft Auto games). The only thing really holding it back is the controls. This game was far ahead of it’s time and because it was limited by the simple joystick and a single button, it made use of lots of keyboard controls, which is far from ideal (this game would probably be a whole lot easier with today’s PS2 style controllers – incidentally, the emulators for the C64 have some strange initial settings which make it difficult to play this game, but that’s a topic for another post.) Still, I had a blast revisiting the game, and it’s something I’d love to see remade with only minor enhancements…

Put simply, it’s a great game. The number of weapons, freedom of movement, varying environments (there are dessert, arctic, and temperate levels), stealth action, variety of missions and randomly generated maps make this game a tough one to beat. Unquestionably my favorite game for the C64, and it would probably end up in my top 10 video games of all time as well.

More screenshots and comments below the fold…

…