A tale of two software projects

A few weeks ago, David Foster wrote an excellent post about two software projects. One was a failure, and one was a success.

The first project was the FBI’s new Virtual Case File system; a tool that would allow agents to better organize, analyze and communicate data on criminal and terrorism cases. After 3 years and over 100 million dollars, it was announced that the system may be totally unusable. How could this happen?

When it became clear that the project was in trouble, Aerospace Corporation was contracted to perform an independent evaluation. It recommended that the software be abandoned, saying that “lack of effective engineering discipline has led to inadequate specification, design and development of VCF.” SAIC has said it believes the problem was caused largely by the FBI: specifically, too many specification changes during the development process…an SAIC executive asserted that there were an average of 1.3 changes per day during the development. SAIC also believes that the current system is useable and can serve as a base for future development.

I’d be interested to see what the actual distribution of changes were (as opposed to the “average changes per day”, which seems awfully vague and somewhat obtuse to me), but I don’t find it that hard to believe that this sort of thing happened (especially because the software development firm was a separate entity). I’ve had some experience with gathering requirements, and it certainly can be a challenge, especially when you don’t know the processes currently in place. This does not excuse anything, however, and the question remains: how could this happen?

The second project, the success, may be able to shed some light on that. DARPA was tapped by the US Army to help protect troops from enemy snipers. The requested application would spot incoming bullets and identify their point of origin, and it would have to be easy to use, mobile, and durable.

The system would identify bullets from their sound..the shock wave created as they travelled through the air. By using multiple microphones and precisely timing the arrival of the “crack” of the bullet, its position could, in theory, be calculated. In practice, though, there were many problems, particularly the high levels of background noise–other weapons, tank engines, people shouting. All these had to be filtered out. By Thanksgiving weekend, the BBN team was at Quantico Marine Base, collecting data from actual firing…in terrible weather, “snowy, freezing, and rainy” recalls DARPA Program Manager Karen Wood. Steve Milligan, BBN’s Chief Technologist, came up with the solution to the filtering problem: use genetic algorithms. These are a kind of “simulated evolution” in which equations can mutate, be tested for effectivess, and sometimes even “mate,” over thousands of simulated generations (more on genetic algorithms here.)

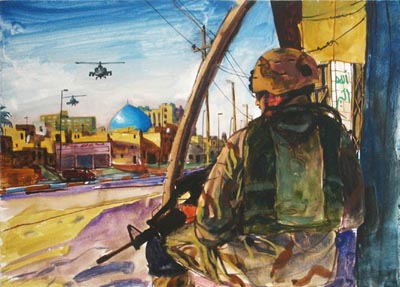

By early March, 2004, the system was operational and had a name–“Boomerang.” 40 of them were installed on vehicles in Iraq. Based on feedback from the troops, improvements were requested. The system has now been reduced in size, shielded from radio interference, and had its display improved. It now tells soldiers the direction, range, and elevation of a sniper.

Now what was the biggest difference between the remarkable success of the Boomerang system and the spectacular failure of the Virtual Case File system? Obviously, the two projects present very different challenges, so a direct comparison doesn’t necessarily tell the whole story. However, it seems to me that discipline (in the case of the Army) or the lack of discipline (in the case of the FBI) might have been a major contributor to the outcomes of these two projects.

It’s obviously no secret that discipline plays a major role in the Army, but there is more to it than just that. Independence and initiative also play an important role in a military culture. In Neal Stephenson’s Cryptonomicon, the way the character Bobby Shaftoe (a Marine Raider, which is “…like a Marine, only more so.”) interacts with his superiors provides some insight (page 113 in my version):

Having now experienced all the phases of military existence except for the terminal ones (violent death, court-martial, retirement), he has come to understand the culture for what it is: a system of etiquette within which it becomes possible for groups of men to live together for years, travel to the ends of the earth, and do all kinds of incredibly weird shit without killing each other or completely losing their minds in the process. The extreme formality with which he addresses these officers carries an important subtext: your problem, sir, is doing it. My gung-ho posture says that once you give the order I’m not going to bother you with any of the details – and your half of the bargain is you had better stay on your side of the line, sir, and not bother me with any of the chickenshit politics that you have to deal with for a living.

Good military officers are used to giving an order, then staying out of their subordinate’s way as they carry out that order. I didn’t see any explicit measurement, but I would assume that there weren’t too many specification changes during the development of the Boomerang system. Of course, the developers themselves made all sorts of changes to specifics and they also incorporated feedback from the Army in the field in their development process, but that is standard stuff.

I suspect that the FBI is not completely to blame, but as the report says, there was a “lack of effective engineering discipline.” The FBI and SAIC share that failure. I suspect, from the number of changes requested by the FBI and the number of government managers involved, that micromanagement played a significant role. As Foster notes, we should be leveraging our technological abilities in the war on terror, and he suggests a loosely based oversight committe (headed by “a Director of Industrial Mobilization”) to make sure things like this don’t happen very often. Sounds like a reasonable idea to me…