In response to my post on Visual Literacy and Rembrandt’s J’accuse, long-time Kaedrin friend Roy made some interesting comments about director Peter Greenaway’s insistence that our ability to analyze visual art forms like paintings is ill-informed and impoverished.

It depends on what you mean by visually illiterate, I guess. Because I think that the majority of people are as visually literate as they are textually literate. What you seem to be comparing is the ability to read into a painting with the ability to read words, but that’s not just reading, you’re talking about analyzing and deconstructing at that point. I mean, most people can watch a movie or look at a picture and do some basic contextualizing. … It’s not for lack of literacy, it’s for lack of training. You know how it is… there’s reading, and then there’s Reading. Most people in the United States know how to read, but that doesn’t mean that they know how to Read. Likewise with visual materials–most people know how to view a painting, they just don’t know how to View a Painting. I don’t think we’re visually illiterate morons, I just think we’re only superficially trained.

I mostly agree with Roy, and I spent most of my post critiquing Greenaway’s film for similar reasons. However, I find the subject of visual literacy interesting. First, as Roy mentions, it depends on how you define the phrase. When we hear the term literacy, we usually mean the ability to read and write, but there’s also a more general definition of being educated or having knowledge within a particular subject or field (i.e. computer literacy or in our case, visual literacy). Greenaway is clearly emphasizing the more general definition. It’s not that he thinks we can’t see a painting, it’s that we don’t know enough about the context of the paintings we are viewing.

Roy is correct to point out that most people actually do have relatively sophisticated visual skills:

Even when people don’t have the vocabulary or training, they still pick up on things, because I think we use symbols and visual language all the time. We read expressions and body language really well, for example. Almost all of our driving rules are encoded first and foremost as symbols, not words–red=stop, green=go, yellow=caution. You don’t need “Stop” or “Yield” on the sign to know which it is–the shape of the sign tells you.

Those are great examples of visual encoding and conventions, but do they represent literacy? Why does a stop sign represent what it does? There are three main components to the stop sign:

- Text – It literally says “Stop” on the sign. However, this is not universal. In Israel, for instance, there is no text. In it’s place is an image of a hand in a “stop” gesture.

- Shape – The octagonal shape of the sign is unique, and so the sign is identifiable even if obscured. The shape also allows drivers facing the back of the sign to identify that oncoming drivers have a stop sign…

- Color – The sign is red, a “hot” color that stands out more than most colors. Blood and fire are red, and red is associated with sin, guilt, passion, and anger, among many other things. As such, red is often used to represent warnings, hence it’s frequent use in traffic signals such as the stop sign.

Interestingly, these different components are overlapping and reinforcing. If one fails (for someone who is color-blind or someone who can’t read, for example), another can still communicate the meaning of the sign. There’s something similar going on with traffic lights, as the position of the light is just as important (if not more important) than the color of the light.

However, it’s worth noting that the clear meaning of a stop sign is also due to the fact that it’s a near universal convention used throughout the entire world. Not all traffic signals are as well defined. Case in point, what does a blinking green traffic light represent? Blinking red means to “stop, then proceed with caution” (kinda like a stop sign). Blinking yellow means to “slow down and proceed with caution.” So what does a blinking green mean? James Grimmelmann tried to figure it out:

It turns out (courtesy of the ODP and rec.travel), perhaps unsurpsingly, that there is no uniform agreement on the meaning of a blinking green light. In a bunch of Canadian provinces, it has the same general meaning that a regular green light does, with the added modifier that you are the undisputed master of all you survey. All other traffic entering the intersection has a stop sign or a red light, and must bow down before your awesome cosmic powers. On the other hand, if you’re in Massachusetts or British Columbia and you try a no-look Ontario-style left turn on a blinking green, you’re liable to get into a smackup, since the blinking green means only that cross traffic is seeing red, with no guarantees about oncoming traffic.

Now, maybe it’s just because we’re starting to get obscure and complicated here, but the reason traffic signals work is because we’ve established a set of conventions that are similar most everywhere. But when we mess around with them or get too complicated, it could be a problem. Luckly, we don’t do that sort of thing very often (even the blinking green example is probably vanishingly obscure – I’ve never seen or even heard of that happening until reading James’ post). These conventions are learned, usually through simple observation, though we also regulate who can drive and require people to study the rules of driving (including signs and lights) before granting a license.

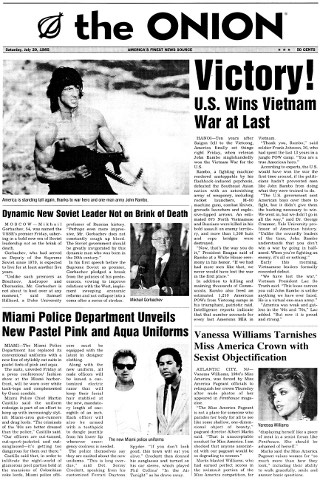

Another example, perhaps surprising because it is something primarily thought of as a textual medium, is newspapers. Take a look at this front page of a newspaper1 :

Newspapers use numerous techniques (such as prominence, grouping, and nesting) to establish a visual hierarchy, allowing readers to scan the page to find what stories they want to read. In the image above, the size of the headline (Victory!) as well as its placement on the page makes it clear at a glance that this is the most important story. The headline “Miami Police Department Unveils New Pastel Pink and Aqua Uniforms” spans three columns of text, making it obvious that they’re all part of the same story. Furthermore, we know the picture of Crockett and Tubbs goes with the same story because both the picture and the text are spanned by the same headline. And so on.

Now I know what my younger readers2 are thinking: What the fuck is this “newspaper” thing you’re babbling about? Well, it turns out that a lot of the same conventions apply to the web. There are, of course, new conventions on the web (for instance, links are usually represented by different colored text that is also underlined), but many of the same techniques are used to establish a visual hierarchy on the web.

What’s more interesting about newspapers and the web is that we aren’t really trained how to read them, but we figure it out anyway. In his excellent book on usability, Don’t Make Me Think, Steve Krug writes:

At some point in our youth, without ever being taught, we all learned to read a newspaper. Not the words, but the conventions.

We learned, for instance, that a phrase in very large type is usually a headline that summarizes the story underneath it, and that the text underneath a picture is either a caption that tells me what it’s a picture of, or – if it’s in very small type – a photo credit that tells me who took the picture.

We learned that knowing the various conventions of page layout and formatting made it easier and faster to scan a newspaper and find the stories we were interested in. And when we started traveling to other cities, we learned that all newspapers used the same conventions (with slight variations), so knowing the conventions made it easy to read any newspaper.

The tricky part about this is that the learning seems to happen subconsciously. Large type is pretty obvious, but column spanning? Captions? Nesting? Some of this stuff gets pretty subtle, and for the most part, people don’t care. They just scan the page, find what they want, and read the story. It’s just intuitive.

But designing a layout is not quite as intuitive. Many of the lessons we have internalized in reading a newspaper (or a website) aren’t really available to us in a situation where we’re asked to design a layout. If you want a good example of this, look at web pages designed in the mid-90s. By now, we’ve got blogs and mini-CMS style systems that automate layouts and take design out of most people’s hands.

So, does Greenaway have a valid point? Or is Roy right? Obviously, we all process visual information, and visual symbolism is frequently used to encode large amounts of information into a relatively small space. Does that make us visually literate? I guess it all comes down to your definition of literate. Roy seems to take the more specific definition of “able to read or write” while Greenaway seems to be more concerned with “education or knowledge in a specified field.” The question then becomes, are we more textually literate than we are visually literate? Greenaway certainly seems to think so. Roy seems to think we’re just about equal on both fronts. I think both positions are defensible, especially when you consider that Greenaway is talking specifically about art. Furthermore, his movie is about a classical painting that was created several centuries ago. For most young people today, art is more diffuse. When you think about it, almost anything can be art. I suspect Greenaway would be disgusted by that sort of attitude, which is perhaps another way to view his thoughts on visual literacy.

1 – Yeah, it’s the Onion and not a real newspaper per say, but it’s fun and it’s representative of common newspaper conventions.

2 – Hahaha, as if I have more than 5 readers, let alone any young readers.

Uh, 26 isn’t considered young? *sniff*

I haven’t watched the documentary, but I got the sense that Greenaway thought that most people would look at that painting and not think about its meaning at all. “Oh, some people standing around, a couple of them are glowing…don’t know who they are, where they are, or what they’re doing…whatever, next please.”

Would you say that’s an accurate read of his attitude? If it is, then he’s definitely wrong. Well, maybe one Renaissance painting doesn’t stand out as being all that interesting amongst a bunch of others from the same period and style to the average person. When I visit art galleries, I don’t ponder the meaning of every piece, but I also don’t just skim everything.

I also don’t read every book that I see, and of the ones I do read, I don’t deeply analyze each one. Greenaway thinks that lack of analysis or deconstruction or investigation is a character flaw and not just a reflection of a person’s likes and dislikes. Not everyone likes reading, not everyone likes art. Plenty of people argue that’s a sad state of affairs, but I’ve always been loathe to judge someone pitiful because sie doesn’t like the exact same things I do.

If Greenaway is saying that there is a greater emphasis in schools on learning to read text, then he is obviously correct. Art and music programs are always the first to be cut, not Literature class. Every single English course in high school was spent reading and analyzing the text, to the annoyance of us students who wanted to be able to just superficially enjoy a book every now and again. But I was only minimally exposed to – not taught – art critique, and the art classes I took focused on technique and working with as many materials as possible.

Still, despite the product of the American public education system, I don’t think that would qualify me and my peers as visually illiterate. I guess that means my definition of “literate” doesn’t require being highly trained or educated. That makes sense because I’ve always been very anti-pedantic when it comes to text and speech. I don’t like so-called grammar Nazis.

If you’re talking about the bit about art, sure, 26 is young (and so is 31 dammit). As for the crack about newspapers, I’m afraid it’s probably not. In fairness, I bet even most kids today still know what a newspaper is, if only as “that thing my mommy and daddy read on sunday mornings” or something.

Anywho, at this point, I’m not sure I’m qualified to interpret exactly what Greenaway is saying. One of the points of my original post was that I was pretty sure he was screwing with his audience in some way. The extent of his shenanigans is difficult to gauge, especially given that he never really explicitly announces that he’s screwing with his audience (it’s just something I suspect).

Greenaway does imply, well, pretty much both of your ideas. One, that people just sorta skim past these paintings without giving it much thought, and that our culture is generally text-based (with schools being a primary example of emphasizing text over art). When he’s talking about this, the screen contains a bunch of people walking past the Night Watch in a museum. I distinctly remember the shot of a woman who was pushing a baby cart and trying to corral another young kid (or something along those lines). She obviously isn’t spending much time pondering the painting. Now, he doesn’t explicitly say that she’s representative of everyone (he doesn’t even talk about her in particular), but it’s sorta implied. I think the second part about a textual culture is actually an interesting point, and it’s part of why I was so interested in this movie. I believe the visual as he’s talking about this is the use of placards next to art that explain the art… through text (again, ironic considering that his movie is narrated with a gigantic amount of text).

If you have netflix, it’s worth watching the first 15-20 minutes (before he starts getting into the “mysteries”) to get a feel for his premise when it comes to this stuff.

In general, while perhaps “literacy” isn’t the right word, I think the general idea of a culture that is more textually based is an interesting point. I have no idea how to quantify it though. What counts as being visually literate or not? Does the stop sign count? Or is that too obvious?

You mention that you don’t skim everything when you go to art galleries. But how often do you go to art galleries? By contrast, how often do you read something semi-significant (i.e. an article, story, etc… something more than just a label or instruction, etc…)

Which is more important in our society: The ability to see, or the ability to read text?

In any case, I agree with most of what you’re saying. Greenaway does come off like a pretentious prick (but again, I think that’s part of his point)…

Hm. I mean, the idea that we tend to emphasize text over images seems obvious; text replicates the language of the land, letting us communicate visually using the language we communicate with verbally.

But we still do a lot with images as well. Anything that has to be built, from the small Lego set, to the tallest building, and everything in between? Images.

Almost anyone involved in a science or math related field is probably working with pictures, too–graphs, charts, diagrams, etc.

And in advertising, images are at least as important as the words. I don’t need the word to know that golden arches mean McDonald’s, right?

Without him having made his point explicitly, it’s hard, because we can’t know what he counts or how strong his claim is. We use non-textual visuals all the time–but a lot of times, it’s done in conjunction with text. We watch films and television, play video games, look at photographs attached to articles, for examples. Do those count to him?

I know I’m all over the place here. =P

Most cultures have a particular emphasis on language, to my understanding, because language allows the most direct lines of communication. I’m not really surprised that our culture would put more effort into teaching language than into being able to deconstruct and interpret images.

Yeah, well, read through my post again. I’m a little all over the place too, and I don’t really have a point, except to babble on about some interesting stuff. I think you should just watch the movie:p It’s on netflix watch instantly, if you have netflix or know someone who does. The stuff we’re talking about all happens within the first 20 minutes or so.