Ladies and gentlemen, we got him

U.S. forces have captured Saddam Hussein. This is exceptional news! And it figures that I had just commented on how intelligence successes are transparent, that we never see them. D’oh! This is a major intelligence victory. We developed an intelligence infrastructure that allowed us to find Hussein, who had burried himself in a hole in a family member’s cellar. We captured him with shovels. This will most likely lead to an intelligence windfall, as already captured Iraqi officals who may have been biting their tongue for fear of Saddam may start talking… (not to mention Saddam himself)

The circumstances of the arrest are about as good as we could ever hope:

- It is speculated that he was turned in by a family member (this is looking less likely, I’m not sure how we found him…)

- Not a single shot fired, not even by Saddam. He had ample opporunity to shoot himself, but he didn’t. That he was captured alive and well will be very beneficial, as it will shut up those conspiracy theorists who would have claimed that it was very convenient that Saddam “killed himself.” I’ve actually seen people who said the same thing about Saddam’s sons express suprise that he was taken alive.

- That it took so long to get him demonstrates just how dedicated and persistent we are when it comes to tracking down someone of Saddam’s importance. I wonder how Osama must feel…

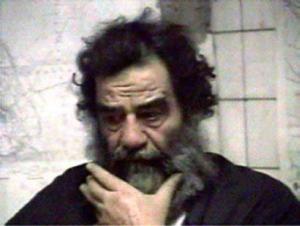

- That his actions were so cowardly (and his visual appearance) will go a long way towards demolishing his image.

This will increase support from the U.S. public as well as support from the Iraqi people. A major worry of Iraqis was that Saddam would come back and punish those who cooperated with the coalition. No more. This will allow the Iraqi people to embrace the new government without fear of retribution from Saddam (though they do still have to worry about the terrorists). And this will represent a major blow to the terrorists. No one knows how involved Hussein was in the attacks against coalition forces, but in almost any scenario, this is bad for the terrorists. I believed Bush to be very vulnerable, but this is big for him. The Democratic candidates have been roundly criticising Bush for this, and this will hurt them.

A lot will depend on how things go from here. The impending trial and how it is executed will be very important. We will also need to make sure Saddam doesn’t kill himself or get killed (a la Goering or Oswald). If he turns up dead, we’ll lose out on a lot.

Lots of others are commenting on this, so here goes:

- Glenn Reynolds: Duh. He has several good posts, including one in which he mentions: “THE LESSON: Saddam’s capture also shows the importance of patience, and of ignoring the kvetching of the Coalition Of The Pissy. While people bitched, the military just kept gathering intelligence and keeping Saddam on the run until he slipped and they caught him.”

- A BBC reporters log: “We all imagined that if the Americans got a tip off they would just bomb somewhere off the face of the earth.” [via Instapundit]

- Steven Den Beste: “He’ll almost certainly end up on trial in an Iraqi tribunal which was created just a few days ago.”

- Merde in France: “Baghdad celebrates, and Paris frowns.”

- Hammorabi: An Iraqi blogger comments

- Baghdad Skies: Another blog run by an Iraqi

- Deeds: CPA member John Galt comments

- Buzz Machine: Lots of good stuff from Jeff Jarvis

- The Command Post: They’re all over this. More here.

- L.T. Smash: A veteran of this war comments and has a good collection of links…

- IRAQ THE MODEL: Iraqi blogger Omar comments: “Thank you American, British, Spanish, Italian, Australian, Ukrainian, Japanese and all the coalition people and all the good people on earth.

God bless the 1st brigade.

God bless the 4th infantry division.

God bless Iraq.

God bless America.

God bless the coalition people and soldiers.

God bless all the freedom loving people on earth.

I wish I could hug you all.”

- Dean Esmay: “Score!” My thoughts exactly!

- Belmont Club: Wretchard comments and makes a good point too: “The magnificence of nations often conceals the smallness of their acts; and from their petty corruptions and idiocies this tapestry of tragedy has been woven.” Saddam wasn’t the only one responsible for the suffering of Iraqis… Look for more from him, as he has proven very insightful…

- Random Jottings: John Weidner comments. “My guess is that they will now sneer that ‘we were promised peace after Saddam was captured.’ Well. Tough luck.”

- Porphyrogenitus: Porphy comments: “Today, for me, is a day of happiness for the people of Iraq, off of whom finally the shadow of Saddam will lift.”

- Winds of Change is on the case…

- The Dissident Frogman: “I’m under the impression that Saddam Hussein would deserve an award for the Most Ridiculous Fall for a Dictator”

- Sneaking Suspicions: Fritz Schrank comments: “And by the way, who told Hussein it was a good idea to try to pass himself off as Ted Kazsynski?” Heheh, check out the picture he has…

- Tacitus: “Got him. Good. Now comes the real fun — weeks and months of debriefing and interrogation at our hands, followed by trial at the hands of his fellow Iraqis. There are so many questions that he can answer: his regime’s true WMD status; the nature of and preparation for the Ba’athist-supported insurgency; the tragically long missing persons list from Kuwait and among his own people; the true extent of his collaboration with terror networks abroad. Psychologically, it will be a fascinating experience — the closest we may ever have come to having a truly Stalinesque personality in the dock. Will he prove himself pliable and brittle, or will sick megalomania impart qualities of fierce resistance?”

- Jim Miller: “I just heard that December 13 may become a national holiday.”

- Donald Sensing: “CNN says that an Iraqi gave the tip to US forces. Only three hours later, we had him.”

- Baghdaddy: He comments: “Early Sunday morning, the U.S. Army delivered to the peoples of the world, an early Christmas present. The capture of Saddam Hussien. There is such celebrating among the general population, that the spirit of Baghdad has changed to one of jubilation. … The celebratory fire, and the smiles on everyones faces is reminisent of the victory scene at the end of Return of The Jedi, when the Death Star was destroyed signifying the end of the Empire. The scene here in Baghdad is truly one worthy of a John Williams soundtrack!” Ha!

- A Small Victory: Michelle has lots of stuff… “We got the bastard!”

- The Messopotamian: Iraqi blogger Alaa comments: “The Baghdadis are expressing what they really think again. Can you hide this now CNN & others? I don?t like swearing, but for those foul friends of the murderers, of all nationalities and kinds, it is like a spike has shot up their asholes to come out of their mouths.”

- Chicago Boyz: Lex comments: “All morning I have been breaking into a smile and Motorhead’s Ace of Spades has been running through my head” Other ChicagoBoyz comment.

- Solport: Don Quixote comments…

- Horsefeathers: Stephen Rittenberg has a roundup of the Democratic candidate’s reactions

- Tim Blair has lots, including a roundup of Aussie reactions…

- Calpundit: Kevin Drum comments

- Joe User/Right Wing Techie: Brad Wardell comments…

- Lee Harris comments “The man who called upon his countrymen and fellow Muslims to sacrifice their own lives in suicide attacks, to blow themselves to bits in order to glorify his name, failed to follow his own instructions. He refused the grand opportunity of a martyr’s death…”

- Boots on the Ground: Kevin, a soldier in Iraq, comments on this and his experiences when Uday and Qusay were killed.

- The End Zone: Hamas is echoing Lee Harris: “CNN reports the head of Palestinian Hamas has issued a statement expressing outrage that Saddam would encourage martrydom in others, yet personally go down without a fight.”

- HipperCritical has an anti-war blogger reaction roundup… [via instapundit]

- Power Line has lots of good info…

- Andrew Olmsted comments with a nice Bull Durham reference: “Yes, it is phenomonal news that Saddam has been captured, and I’ve been fairly bouncing up and down with excitement since I heard the news. … But as good as this news is, this moment, too, is over.”

- Wolverines!

Gah! Information overload! I could probably find a million other links to put here. Perhaps more later…

Update: I’ve been updating the link list like crazy…

V is for Victory! |

A Thumbs up from Kuwaitis |

Update: Dean Esmay steals my picture! Hee hee. He’s got more good stuff as well..

Update 12.15.03: And I thought yesterday represented information overload. Tons of new stuff appearing today, much of it excellent, and a lot of it having to do with the challenge of what to do with Hussein…

- Belmont Club: I told you so – another excellent and insightful article today which examines the strengths of Saddam’s current position.

- Chicago Boyz: Along the same lines, Lex questions the assumption that “it will go well for the ‘prosecution’ and end without too much hassle in Saddam’s execution.”

- Stephen Den Beste weighs in on the situation, focusing more on the success of US intelligence and the importance and effects of what we do with Saddam.

- Ralph Peters also talks about the intelligence successes in Iraq.