Vintage Science Fiction Month is the brainchild of the Little Red Reviewer. The objective: Read and discuss “older than I am” Science Fiction in the month of January.

These are the voyages of the Space Beagle. It’s continuing mission: to explore intergalactic space, encounter new life forms, new civilizations, and survive their deadly advances. Yes, A.E. van Vogt’s Voyage of the Space Beagle is a pretty clear precursor to Star Trek, right down to the episodic nature of the narrative. Of course, that’s mostly because this is a prime example of what was called a “fix-up” novel, a book comprised of a compilation of four previously published stories. The title of the book is also a pretty clear reference to Charles Darwin’s book about his five-year mission (another Trek connection) of scientific exploration on the HMS Beagle.

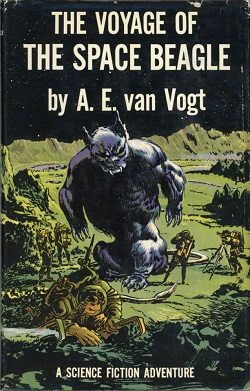

The first story details an encounter with Coeurl, a starving, intelligent cat-like creature that plays dumb in order to trick the crew of the Space Beagle into allowing access to the ship. Several members of the crew are killed before they wise up and manage to trick the beast into an escape capsule and strand it in space.

The second story follows the chaos resulting from telepathic contact with a race of bird-like aliens. One member of the crew recognizes that the signals are meant to be a benign, friendly message, but the form of the message is incompatible with the human mind, and only quick actions by the aforementioned crew member saves the ship.

The third story has the Space Beagle picking up a red creature called Ixtl, which seeks to reproduce by kidnapping members of the crew and implanting eggs in them. Some details of this story are close enough to the film Alien that van Vogt actually sued for plagiarism (the case settled out of court, and for the record, the filmmakers deny any influence).

Finally, the fourth story shows an encounter with a galaxy-spanning consciousness that has, more or less, consumed its entire galaxy. The crew must devise some sort of strategy to deal with this situation, especially given that they don’t want to lead this entity back to our home galaxy.

In fixing these stories up for the novel, van Vogt would establish a new central character, Elliot Grosvenor, the lone “Nexialist” onboard the Space Beagle. Nexialism is van Vogt’s name for a sorta holistic approach to knowledge. As he describes:

Nexialism is the science of joining in an orderly fashion the knowledge of one field of learning with that of other fields. It provides techniques for speeding up the processes of absorbing knowledge and of using effectively what has been learned.

…

The problems which Nexialism confronts are whole problems. Man has divided life and matter into separate compartments of knowledge and being. And, even though he sometimes uses words which indicate his awareness of the wholeness of nature, he continues to behave as if the one, changing universe had many separately functioning parts.

In essence, Grossvenor is van Vogt’s equivalent of Heinlein’s competent man. As Heinlein famously quipped, “Specialization is for insects.” At times, you can feel the “fix-up” nature of the novel, as it seems Grossvenor fades too much into the background of the narrative. Also, though the stories have satisfactory conclusions, they do feel a bit repetitive, and while the holistic approach of Nexialism is certainly admirable, the solutions aren’t quite clever enough to really justify the idea. Still, there’s something fundamentally optimistic about van Vogt’s vision that is refreshing in this cynical age. It’s telling that the alien creatures are all undone by their own egotism and selfishness, while the crew of the Space Beagle prevail through decency, self-sacrifice, and cooperation. Of course, there’s plenty of infighting amongst various specialized factions of the crew, but that’s the point of Grossvenor’s holistic approach.

This is almost certainly one of those books that suffers due to it’s influence. So much of what has followed in its footsteps have improved on the ideas that going back to read this now makes it feel quaint. It is certainly an interesting exercise to see such ideas in their embryonic form, even if the terminology used can be a bit stiff or even laughable (the crew repeatedly brandish a weapon that van Vogt calls a “vibrator” – it’s not his fault that the term has taken on other meanings since then, but still), but at this point, it’s probably more suitable for students of the genre than anyone else.

None of which is to say that the novel is bad, per say, just that it doesn’t quite hang together as well as you would generally want from a novel. Not entirely unexpected, given the “fix-up” nature of the novel, but it’s ironic that a novel with the theme that holistic thought is critical would be so episodic and disjointed. From what I can tell, van Vogt’s concept of Nexialism lead him to start thinking about how humankind would need to transcend its limitations, and thus followed Space Beagle up with the novel Slan, which represents a more cohesive vision from van Vogt. Still, if you want to see how early Space Opera stories influenced much of the current Science Fiction landscape, Voyage of the Space Beagle is a pretty good place to start (if perhaps not the earliest).