Vintage Science Fiction Month is the brainchild of the Little Red Reviewer. The objective: Read and discuss “older than I am” Science Fiction in the month of January.

In The Lincoln Hunters, time travel exists for people 700 years in the future, but it is primarily used for historical information gathering purposes and museum-like desires to preserve same. Ben Steward is a Character; basically a time-traveling agent who acts as if he’s a member of the time-period he’s visiting so as to facilitate whatever history-recording task he may have. His latest mission: attend and record Abraham Lincoln’s famous Lost Speech, delivered at the Anti-Nebraska State Convention in Bloomington, Illinois on May 29, 1856.

On his first scouting mission, the time travel engineers overshoot their target and send him to the day after the event he’s trying to capture (rather than the day before). As such, he’s actually scouting in the aftermath of his mission. This has all sorts of implications, but from a storytelling perspective, it sets the stakes rather effectively. Steward is recognized by certain personages, he finds evidence of a snafu with the mission, and thanks to the (admittedly vague) rules of time travel, his next trip to the past (with a team of other Characters set to record Lincoln’s speech) is now time-bound because the same person cannot inhabit the same time at the, uh, same time.

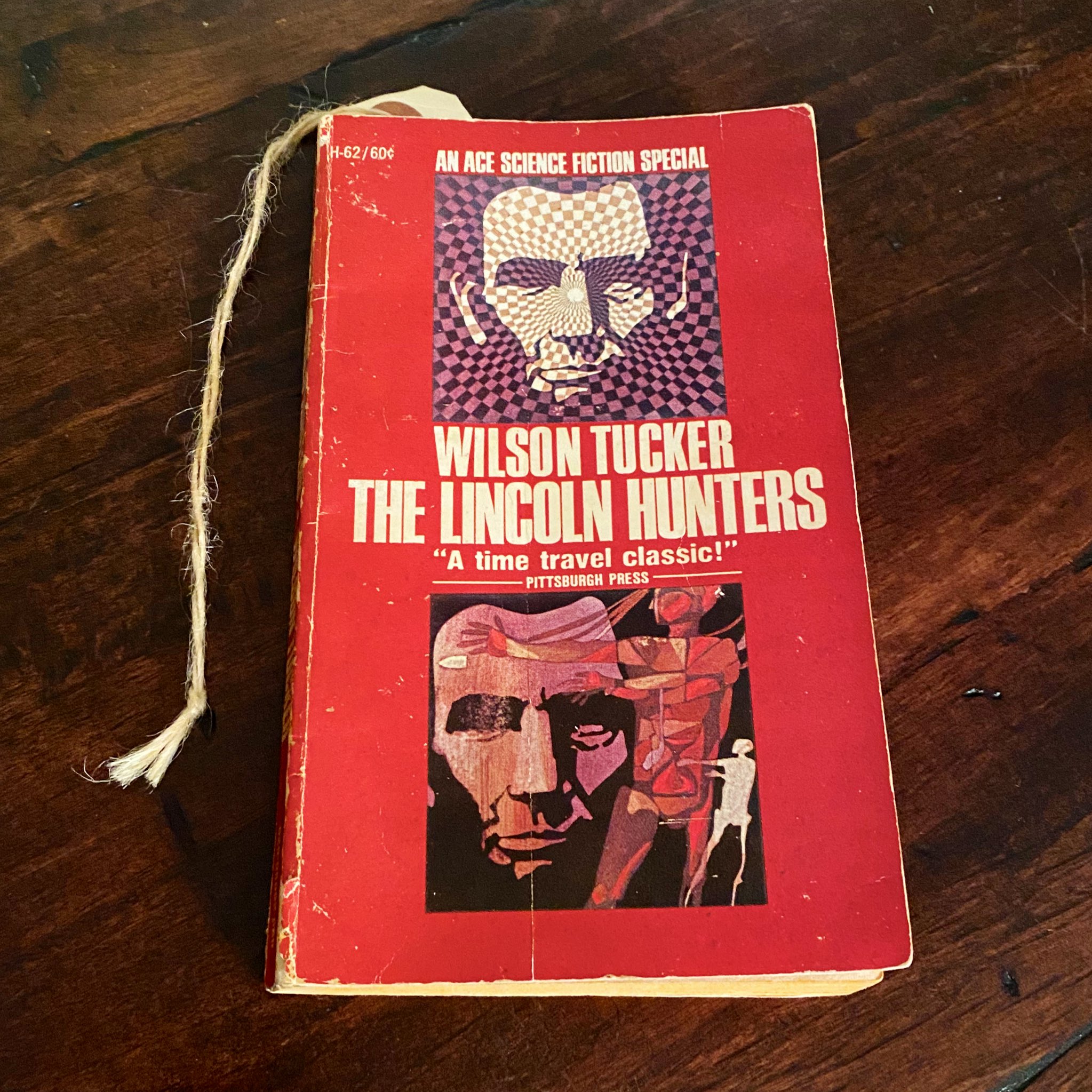

It’s an effective setup, and author Wilson Tucker mostly plays it as a straight adventure story with some SF complications. Alas, this does represent a bit of a lost opportunity, as there’s a lot of thematic potential here that goes unexplored. For that matter, even the time travel mechanics are a little on the vague side. There is, of course, plenty of info-dumping up front, such as this bit explaining why Characters are taught the history leading up to their arrival, but not anything after:

“…the abstract ceased abruptly as near as possible to the target date itself. That was standard operating procedure designed to protect the Character and the assignment. It would not do for a man in the field to know the events of coming weeks or even years – his tongue might slip. To retain his value as a Character, he must be as wise, and as ignorant as the local people around him.”

The Lincoln Hunters (page 30)

However, as the story progresses, the exploration of time-travel mechanics gets left behind, instead relying on more vague assertions that something bad will happen if they don’t make it back home in time, follow certain other strict rules, etc… All well and good for the story and pacing, but it might leave something to be desired from a rigor standpoint.

There are plenty of fun little historical asides to be had, of course, such as this one:

“… He left a short time ago, to record a New Year’s Eve celebration in the year 2000, O.N. A place called Times Square. The client wishes to determine whether the century began with 2000, or 2001.”

The Lincoln Hunters (page 23)

Remember the pedants insisting that the century didn’t really start until 2001? It’s funny that Tucker anticipated that debate 40+ years earlier. Another fun bit of trivia is that one of the characters, Bobby Bloch, is actually named after Robert Bloch, a friend of Tucker’s and a fellow author who was about to become famous for writing a little novel called Psycho. This practice of including a friend’s name in your text as an in-joke is actually called Tuckerization, named after Tucker himself. But I digress…

It’s also worth noting that Lincoln’s Lost Speech is a real and seemingly pivotal event. We really don’t know the exact contents of the speech, so it would be an enticing destination for future historians. What we do know is that it sits at the fulcrum of several key historical events: the dissolution of the Whig party, the formation of the Republican party, Lincoln’s ascendency to the presidency, and eventually the Civil War itself. Tucker embeds lots of other real historical figures into the story as well, even including more obscure people like Owen Lovejoy (who Steward seems to have run afoul of in his, uh, future trip to the past).

Lincoln’s lost speech and the themes it presumably emphasized stand in stark contrast to the future that Tucker presents, but the comparison is mostly left as an exercise for the reader. The future appears to be very regimented and even includes references to things like “labor camps”, which seems like a ripe target for a more extended exploration of the analogy between Lincoln’s time and the future. Alas, like time-travel itself, this mostly takes a back seat to what essentially amounts to an adventure story. It’s there and I certainly managed to connect the dots, but Tucker could have probably squeezed more juice out of this premise without sacrificing much in the way of pacing or excitement.

For its part, the adventure plot is reasonably well done. Tucker sets up a few things during the scouting mission that come to fruition in the mission proper, and there’s always something satisfying about puzzle pieces coming together in that way. That said, it’s not a particularly complicated puzzle, and the ultimate ending leaves something to be desired. You might get some small hits of that vaunted “sense of wonder” that makes SF so fun, but it’s not going to blow you away either.

The Lincoln Hunters is a fun little time travel story. Short and sweet, it doesn’t have much explicit depth, but it kept me reasonably entertained for its short (less than 200 page) length. I can’t say as though it ranks among my favorite time-travel stories, but it has its moments, and folks familiar with the time-period might get an extra kick out of it. As such, it is an interesting exhibit in the “Science Fiction geeks often turn into history buffs” wing of the genre.