“To write or to speak is almost inevitably to lie a little. It is an attempt to clothe an intangible in a tangible form; to compress an immeasurable into a mold. And in the act of compression, how the Truth is mangled and torn!”

– Anne Murrow Lindbergh

There are many types of documentary films. The most common form of documentary is referred to as Direct Address (aka Voice of God). In such a documentary, the viewer is directly acknowledged, usually through narration and voice-overs. There is very little ambiguity and it is pretty obvious how you’re expected to interpret these types of films. Many television and news programs use this style, to varying degrees of success. Ken Burns’ infamous Civil War and Baseball series use this format eloquently, but most traditional propaganda films also fall into this category (a small caveat: most films are hybrids, rarely falling exclusively into one category). Such films give the illusion of being an invisible witness to certain events and are thus very persuasive and powerful.

The problem with Direct Address documentaries is that they grew out of a belief that Truth is knowable through objective facts. In a recent sermon he posted on the web, Donald Sensing spoke of the difference between facts and the Truth:

Truth and fact are not the same thing. We need only observe the presidential race to discern that. John Kerry and allies say that the results of America’s war against Iraq is mostly a failure while George Bush and allies say they are mostly success. Both sides have the same facts, but both arrive at a different “truth.”

People rarely fight over facts. What they argue about is what the facts mean, what is the Truth the facts indicate.

I’m not sure Sensing chose the best example here, but the concept itself is sound. Any documentary is biased in the Truth that it presents, even if the facts are undisputed. In a sense objectivity is impossible, which is why documentary scholar Bill Nichols admires films which seek to contextualize themselves, exposing their limitations and biases to the audience.

Reflexive Documentaries use many devices to acknowledge the filmmaker’s presence, perspective, and selectivity in constructing the film. It is thought that films like this are much more honest about their subjectivity, and thus provide a much greater service to the audience.

An excellent example of a Reflexive documentary is Errol Morris’ brilliant film, The Thin Blue Line. The film examines the “truth” around the murder of a Dallas policeman. The use of colored lighting throughout the film eventually correlates with who is innocent or guilty, and Morris is also quite manipulative through his use of editing – deconstructing and reconstructing the case to demonstrate just how problematic finding the truth can be. His use of framing calls attention to itself, daring the audience to question the intents of the filmmakers. The use of interviews in conjunction with editing is carefully structured to demonstrate the subjectivity of the film and its subjects. As you watch the movie, it becomes quite clear that Morris is toying with you, the viewer, and that he wants you to be critical of the “truth” he is presenting.

Ironically, a documentary becomes more objective when it acknowledges its own biases and agenda. In other words, a documentary becomes more objective when it admits its own subjectivity. There are many other forms of documentary not covered here (i.e. direct cinema/cinema verité, interview-based, performative, mock-documentaries, etc… most of which mesh together as they did in Morris’ Blue Line to form a hybrid).

In Bill Nichols’ seminal essay, Voice of Documentary (Can’t seem to find a version online), he says:

“Documentary filmmakers have a responsibility not to be objective. Objectivity is a concept borrowed from the natural sciences and from journalism, with little place in the social sciences or documentary film.”

I always found it funny that Nichols equates the natural sciences with journalism, as it seems to me that modern journalism is much more like a documentary than a natural science. As such, I think the lessons of Reflexive documentaries (and its counterparts) should apply to the realm of journalism.

The media emphatically does not acknowledge their biases. By bias, I don’t mean anything as short-sighted as liberal or conservative media bias, I mean structural bias of which political orientation is but a small part (that link contains an excellent essay on the nature of media bias, one that I find presents a more complete picture and is much more useful than the tired old ideological bias we always hear so much about*). Such subjectivity does exist in journalism, yet the media stubbornly persists in their firm belief that they are presenting the objective truth.

The recent CBS scandal, consisting of a story bolstered by what appear to be obviously forged documents, provides us with an immediate example. Terry Teachout makes this observation regarding how few prominent people are willing to admit that they are wrong:

I was thinking today about how so few public figures are willing to admit (for attribution, anyway) that they’ve done something wrong, no matter how minor. But I wasn’t thinking of politicians, or even of Dan Rather. A half-remembered quote had flashed unexpectedly through my mind, and thirty seconds’ worth of Web surfing produced this paragraph from an editorial in a magazine called World War II:

Soon after he had completed his epic 140-mile march with his staff from Wuntho, Burma, to safety in India, an unhappy Lieutenant General Joseph W. Stilwell was asked by a reporter to explain the performance of Allied armies in Burma and give his impressions of the recently concluded campaign. Never one to mince words, the peppery general responded: “I claim we took a hell of a beating. We got run out of Burma and it is as humiliating as hell. I think we ought to find out what caused it, and go back and retake it.”

Stilwell spoke those words sixty-two years ago. When was the last time that such candor was heard in like circumstances? What would happen today if similar words were spoken by some equally well-known person who’d stepped in it up to his eyebrows?

As he points out later in his post, I don’t think we’re going to be seeing such admissions any time soon. Again, CBS provides a good example. Rather than admit the possibility that they may be wrong, their response to the criticisms of their sources has been vague, dismissive, and entirely reliant on their reputation as a trustworthy staple of journalism. They have not yet comprehensively responded to any of the numerous questions about the documents; questions which range from “conflicting military terminology to different word-processing techniques”. It appears their strategy is to escape the kill zone by focusing on the “truth” of their story, that Bush’s service in the Air National Guard was less than satisfactory. They won’t admit that the documents are forgeries, and by focusing on the arguably important story, they seek to distract the issue away from their any discussion of their own wrongdoing – in effect claiming that the documents aren’t important because the story is “true” anyway.

Should they admit they were wrong? Of course they should, but they probably won’t. If they won’t, it will not be because they think the story is right, and not because they think the documents are genuine. They won’t admit wrongdoing and they won’t correct their methodologies or policies because to do so would be to acknowledge to the public that they are less than just an objective purveyor of truth.

Yet I would argue that they should do so, that it is their duty to do so just as it is the documentarian’s responsibility to acknowledge their limitations and agenda to their audience.

It is also interesting to note that weblogs contrast the media by doing just that. Glenn Reynolds notes that the internet is a low-trust medium, which paradoxically indicates that it is more trustworthy than the media (because blogs and the like acknowledge their bias and agenda, admit when they’re wrong, and correct their mistakes):

The Internet, on the other hand, is a low-trust environment. Ironically, that probably makes it more trustworthy.

That’s because, while arguments from authority are hard on the Internet, substantiating arguments is easy, thanks to the miracle of hyperlinks. And, where things aren’t linkable, you can post actual images. You can spell out your thinking, and you can back it up with lots of facts, which people then (thanks to Google, et al.) find it easy to check. And the links mean that you can do that without cluttering up your narrative too much, usually, something that’s impossible on TV and nearly so in a newspaper.

(This is actually a lot like the world lawyers live in — nobody trusts us enough to take our word for, well, much of anything, so we back things up with lots of footnotes, citations, and exhibits. Legal citation systems are even like a primitive form of hypertext, really, one that’s been around for six or eight hundred years. But I digress — except that this perhaps explains why so many lawyers take naturally to blogging).

You can also refine your arguments, updating — and even abandoning them — in realtime as new facts or arguments appear. It’s part of the deal.

This also means admitting when you’re wrong. And that’s another difference. When you’re a blogger, you present ideas and arguments, and see how they do. You have a reputation, and it matters, but the reputation is for playing it straight with the facts you present, not necessarily the conclusions you reach.

The mainstream media as we know it is on the decline. They will no longer be able to get by on their brand or their reputations alone. The collective intelligence of the internet, combined with the natural reflexiveness of its environment, has already provided a challenge to the underpinnings of journalism. On the internet, the dominance of the media is constantly challenged by individuals who question the “truth” presented to them in the media. I do not think that blogs have the power to eclipse the media, but their influence is unmistakable. The only question that remains is if the media will rise to the challenge. If the way CBS has reacted is any indication, then, sadly, we still have a long way to go.

* Yes, I do realize the irony of posting this just after I posted about liberal and conservative tendencies in online debating, and I hinted at that with my “Update” in that post.

Thanks to Jay Manifold for the excellent Structural Bias of Journalism link.

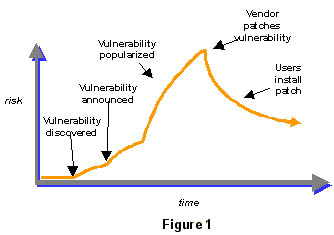

Phase 1 is before the vulnerability is discovered. The vulnerability exists, but no one can exploit it. Phase 2 is after the vulnerability is discovered, but before it is announced. At that point only a few people know about the vulnerability, but no one knows to defend against it. Depending on who knows what, this could either be an enormous risk or no risk at all. During this phase, news about the vulnerability spreads — either slowly, quickly, or not at all — depending on who discovered the vulnerability. Of course, multiple people can make the same discovery at different times, so this can get very complicated.

Phase 1 is before the vulnerability is discovered. The vulnerability exists, but no one can exploit it. Phase 2 is after the vulnerability is discovered, but before it is announced. At that point only a few people know about the vulnerability, but no one knows to defend against it. Depending on who knows what, this could either be an enormous risk or no risk at all. During this phase, news about the vulnerability spreads — either slowly, quickly, or not at all — depending on who discovered the vulnerability. Of course, multiple people can make the same discovery at different times, so this can get very complicated.