Last week, I wrote about the paradox of choice: having too many options often leads to something akin to buyer’s remorse (paralysis, regret, dissatisfaction, etc…), even if their choice was ultimately a good one. I had attended a talk given by Barry Schwartz on the subject (which he’s written a book about) and I found his focus on the psychological impact of making decisions fascinating. In the course of my ramblings, I made an offhand comment about computers and software:

… the amount of choices in assembling your own computer can be stifling. This is why computer and software companies like Microsoft, Dell, and Apple (yes, even Apple) insist on mediating the user’s experience with their hardware & software by limiting access (i.e. by limiting choice). This turns out to be not so bad, because the number of things to consider really is staggering.

The foolproofing that these companies do can sometimes be frustrating, but for the most part, it works out well. Linux, on the other hand, is the poster child for freedom and choice, and that’s part of why it can be a little frustrating to use, even if it is technically a better, more stable operating system (I’m sure some OSX folks will get a bit riled with me here, but bear with me). You see this all the time with open source software, especially when switching from regular commercial software to open source.

One of the admirable things about Linux is that it is very well thought out and every design decision is usually done for a specific reason. The problem, of course, is that those reasons tend to have something to do with making programmers’ lives easier… and most regular users aren’t programmers. I dabble a bit here and there, but not enough to really benefit from these efficiencies. I learned most of what I know working with Windows and Mac OS, so when some enterprising open source developer decides that he doesn’t like the way a certain Windows application works, you end up seeing some radical new design or paradigm which needs to be learned in order to use it. In recent years a lot of work has gone into making Linux friendlier for the regular user, and usability (especially during the installation process) has certainly improved. Still, a lot of room for improvement remains, and I think part of that has to do with the number of choices people have to make.

Let’s start at the beginning and take an old Dell computer that we want to install Linux on (this is basically the computer I’m running right now). First question: which distrubution of Linux do we want to use? Well, to be sure, we could start from scratch and just install the Linux Kernel and build upwards from there (which would make the process I’m about to describe even more difficult). However, even Linux has it’s limits, so there are lots of distrubutions of linux which package the OS, desktop environments, and a whole bunch of software together. This makes things a whole lot easier, but at the same time, there are a ton of distrutions to choose from. The distributions differ in a lot of ways for various reasons, including technical (issues like hardware support), philosophical (some distros poo poo commercial involvement) and organizational (things like support and updates). These are all good reasons, but when it’s time to make a decision, what distro do you go with? Fedora? Suse? Mandriva? Debian? Gentoo? Ubuntu? A quick look at Wikipedia reveals a comparison of Linux distros, but there are a whopping 67 distros listed and compared in several different categories. Part of the reason there are so many distros is that there are a lot of specialized distros built off of a base distro. For example, Ubuntu has several distributions, including Kubuntu (which defaults to the KDE desktop environment), Edubuntu (for use in schools), Xubuntu (which uses yet another desktop environment called Xfce), and, of course, Ubuntu: Christian Edition (linux for Christians!).

So here’s our first choice. I’m going to pick Ubuntu, primarily because their tagline is “Linux for Human Beings” and hey, I’m human, so I figure this might work for me. Ok, and it has a pretty good reputation for being an easy to use distro focused more on users than things like “enterprises.”

Alright, the next step is to choose a desktop environment. Lucky for us, this choice is a little easier, but only because Ubuntu splits desktop environments into different distributions (unlike many others which give you the choice during installation). For those who don’t know what I’m talking about here, I should point out that a desktop environment is basically an operating system’s GUI – it uses the desktop metaphor and includes things like windows, icons, folders, and abilities like drag-and-drop. Microsoft Windows and Mac OSX are desktop environments, but they’re relatively locked down (to ensure consistency and ease of use (in theory, at least)). For complicated reasons I won’t go into, Linux has a modular system that allows for several different desktop environments. As with linux distributions, there are many desktop environments. However, there are really only two major players: KDE and Gnome. Which is better appears to be a perennial debate amongst linux geeks, but they’re both pretty capable (there are a couple of other semi-popular ones like Xfce and Enlightenment, and then there’s the old standby, twm (Tom’s Window Manager)). We’ll just go with the default Gnome installation.

Note that we haven’t even started the installation process and if we’re a regular user, we’ve already made two major choices, each of which will make you wonder things like: Would I have this problem if I installed Suse instead of Ubuntu? Is KDE better than Gnome?

But now we’re ready for installation. This, at least, isn’t all that bad, depending on the computer you’re starting with. Since we’re using an older Dell model, I’m assuming that the hardware is fairly standard stuff and that it will all be supported by my distro (if I were using a more bleeding edge type box, I’d probably want to check out some compatibility charts before installing). As it turns out, Ubuntu and it’s focus on creating a distribution that human beings can understand has a pretty painless installation. It was actually a little easier than Windows, and when I was finished, I didn’t have to remove the mess of icons and trial software offers (purchasing a Windows PC through somone like HP is apparently even worse). When you’re finished installing Ubuntu, you’re greeted with a desktop that looks like this (click the pic for a larger version):

No desktop clutter, no icons, no crappy trial software. It’s beautiful! It’s a little different from what we’re used to, but not horribly so. Windows users will note that there are two bars, one on the top and one on the bottom, but everything is pretty self explanatory and this desktop actually improves on several things that are really strange about Windows (i.e. to turn off you’re computer, first click on “Start!”). Personally, I think having two toolbars is a bit much so I get rid of one of them, and customize the other so that it has everything I need (I also put it at the bottom of the screen for several reasons I won’t go into here as this entry is long enough as it is).

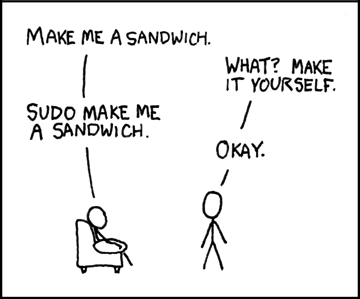

Alright, we’re almost homefree, and the installation was a breeze. Plus, lots of free software has been installed, including Firefox, Open Office, and a bunch of other good stuff. We’re feeling pretty good here. I’ve got most of my needs covered by the default software, but let’s just say we want to install Amarok, so that we can update our iPod. Now we’re faced with another decision: How do we install this application? Since Ubuntu has so thoughtfully optimized their desktop for human use, one of the things we immediately notice in the “Applications” menu is an option which says “Add/Remove…” and when you click on it, a list of software comes up and it appears that all you need to do is select what you want and it will install it for you. Sweet! However, the list of software there doesn’t include every program, so sometimes you need to use the Synaptic package manager, which is also a GUI application installation program (though it appears to break each piece of software into smaller bits). Also, in looking around the web, you see that someone has explained that you should download and install software by typing this in the command line: apt-get install amarok. But wait! We really should be using the aptitude command instead of apt-get to install applications.

If you’re keeping track, that’s four different ways to install a program, and I haven’t even gotten into repositories (main, restricted, universe, multiverse, oh my!), downloadable package files (these operate more or less the way a Windows user would download a .exe installation file, though not exactly), let alone downloading the source code and compiling (sounds fun, doesn’t it?). To be sure, they all work, and they’re all pretty easy to figure out, but there’s little consistency, especially when it comes to support (most of the time, you’ll get a command line in response to a question, which is completely at odds with the expectations of someone switching from Windows). Also, in the case of Amarok, I didn’t fare so well (for reasons belabored in that post).

Once installed, most software works pretty much the way you’d expect. As previously mentioned, open source developers sometimes get carried away with their efficiencies, which can sometimes be confusing to a newbie, but for the most part, it works just fine. There are some exceptions, like the absurd Blender, but that’s not necessarily a hugely popular application that everyone needs.

Believe it or not, I’m simplifying here. There are that many choices in Linux. Ubuntu tries its best to make things as simple as possible (with considerable success), but when using Linux, it’s inevitable that you’ll run into something that requires you to break down the metaphorical walls of the GUI and muck around in the complicated swarm of text files and command lines. Again, it’s not that difficult to figure this stuff out, but all these choices contribute to the same decision fatigue I discussed in my last post: anticipated regret (there are so many distros – I know I’m going to choose the wrong one), actual regret (should I have installed Suse?), dissatisfaction, excalation of expectations (I’ve spent so much time figuring out what distro to use that it’s going to perfectly suit my every need!), and leakage (i.e. a bad installation process will affect what you think of a program, even after installing it – your feelings before installing leak into the usage of the application).

None of this is to say that Linux is bad. It is free, in every sense of the word, and I believe that’s a good thing. But if they ever want to create a desktop that will rival Windows or OSX, someone needs to create a distro that clamps down on some of these choices. Or maybe not. It’s hard to advocate something like this when you’re talking about software that is so deeply predicated on openess and freedom. However, as I concluded in my last post:

Without choices, life is miserable. When options are added, welfare is increased. Choice is a good thing. But too much choice causes the curve to level out and eventually start moving in the other direction. It becomes a matter of tradeoffs. Regular readers of this blog know what’s coming: We don’t so much solve problems as we trade one set of problems for another, in the hopes that the new set of problems is more favorable than the old.

Choice is a double edged sword, and by embracing that freedom, Linux has to deal with the bad as well as the good (just as Microsoft and Apple have to deal with the bad aspects of suppressing freedom and choice). Is it possible to create a Linux distro that is as easy to use as Windows or OSX while retaining the openness and freedom that makes it so wonderful? I don’t know, but it would certainly be interesting.