Polarized Debate

This is yet another in a series of posts fleshing out ideas initially presented in a post regarding Reflexive Documentary filmmaking and the media. In short, Reflexive Documentaries achieve a higher degree of objectivity by embracing and acknowledging their own biases and agenda. Ironically, by acknowledging their own subjectivity, these films are more objective and reliable. I expanded the scope of the concepts originally presented in that post to include a broader range of information dissemination processes, which lead to a post on computer security and a post on national security.

I had originally planned to apply the same concepts to debating in a relatively straightforward manner. I’ll still do that, but recent events have lead me to reconsider my position, thus there will most likely be some unresolved questions at the end of this post.

So the obvious implication with respect to debating is that a debate can be more productive when each side exposes their own biases and agenda in making their argument. Of course, this is pretty much required by definition, but what I’m getting at here is more a matter of tactics. Debating tactics often take poor forms, with participants scoring cheap points by using intuitive but fallacious arguments.

I’ve done a lot of debating in various online forums, often taking a less than popular point of view (I tend to be a contrarian, and am comofortable on the defense). One thing that I’ve found is that as a debate heats up, the arguments become polarized. I sometimes find myself defending someone or something that I normally wouldn’t. This is, in part, because a polarizing debate forces you to dispute everything your opponent argues. To concede one point irrevocably weakens your position, or so it seems. Of course, the fact that I’m a contrarian, somewhat competitive, and stubborn also plays a part this. Emotions sometimes flare, attitudes clash, and you’re often left feeling dirty after such a debate.

None of which is to say that polarized debate is bad. My whole reason for participating in such debates is to get others to consider more than one point of view. If a few lurkers read a debate and come away from it confused or at least challenged by some of the ideas presented, I consider that a win. There isn’t anything inherently wrong with partisanship, and as frustrating as some debates are, I find myself looking back on them as good learning experiences. In fact, taking an extreme position and thinking from that biased standpoint helps you understand not only that viewpoint, but the extreme opposite as well.

The problem with such debates, however, is that they really are divisive. A debate which becomes polarized might end up providing you with a more balanced view of an issue, but such debates sometimes also present an unrealistic view of the issue. An example of this is abortion. Debates on that topic are usually heated and emotional, but the issue polarizes, and people who would come down somewhere around the middle end up arguing an extreme position for or against.

Again, I normally chalk this polarization up as a good thing, but after the election, I’m beginning to see the wisdom in perhaps pursuing a more moderated approach. With all the red/blue dichotomies being thrown around with reckless abandon, talk of moving to Canada and even talk of secesssion(!), it’s pretty obvious that the country has become overly-polarized.

I’ve been writing about Benjamin Franklin recently on this here blog, and I think his debating style is particularly apt to this discussion:

Franklin was worried that his fondness for conversation and eagerness to impress made him prone to “prattling, punning and joking, which only made me acceptable to trifling company.” Knowledge, he realized, “was obtained rather by the use of the ear than of the tongue.” So in the Junto, he began to work on his use of silence and gentle dialogue.

One method, which he had developed during his mock debates with John Collins in Boston and then when discoursing with Keimer, was to pursue topics through soft, Socratic queries. That became the preferred style for Junto meetings. Discussions were to be conducted “without fondness for dispute or desire of victory.” Franklin taught his friends to push their ideas through suggestions and questions, and to use (or at least feign) naive curiousity to avoid contradicting people in a manner that could give offense. … It was a style he would urge on the Constitutional Convention sixty years later. [This is an exerpt from the recent biography Benjamin Franklin: An American Life by Walter Isaacson]

This contrasts rather sharply with what passes for civilized debate these days. Franklin actually considered it rude to directly contradict or dispute someone, something I had always found to be confusing. I typically favor a frank exchange of ideas (i.e. saying what you mean), but I’m beginning to come around. In the wake of the election, a lot of advice has been offered up for liberals and the left, and a lot of suggestions center around the idea that they need to “reach out” to more voters. This has been recieved with indignation by liberals and leftists, and one could hardly blame them. From their perspective, conservatives and the right are just as bad if not worse and they read such advice as if they’re being asked to give up their values. Irrespective of which side is right, I think the general thrust of the advice is that liberal arguments must be more persuasive. No matter how much we might want to paint the country into red and blue partitions, if you really want to be accurate, you’d see only a few small areas of red and blue drowning in a sea of purple. The Democrats don’t need to convince that many people to get a more favorable outcome in the next election.

And so perhaps we should be fighting the natural polarization of a debate and take a cue from Franklin, who stressed the importance of deferring, or at least pretending to defer, to others:

“Would you win the hearts of others, you must not seem to vie with them, but to admire them. Give them every opportunity of displaying their own qualifications, and when you have indulged their vanity, they will praise you in turn and prefer you above others… Such is the vanity of mankind that minding what others say is a much surer way of pleasing them than talking well ourselves.”

There are weaknesses to such an approach, especially if your opponent does not return the favor, but I think it is well worth considering. That the country has so many opposing views is not necessarily bad, and indeed, is a necessity in democracy for ideas to compete. But perhaps we need less spin and more moderation… In his essay “Apology for Printers” Franklin opines:

“Printers are educated in the belief that when men differ in opinion, both sides ought equally to have the advantage of being heard by the public; and that when Truth and Error have fair play, the former is always an overmatch for the latter.”

Indeed.

Update: Andrew Olmsted posted something along these lines, and he has a good explanation as to why debates often go south:

I exaggerate for effect, but anyone spending much time on site devoted to either party quickly runs up against the assumption that the other side isn’t just wrong, but evil. And once you’ve made that assumption, it would be wrong to even negotiate with the other side, because any compromise you make is taking the country one step closer to that evil. The enemy must be fought tooth and nail, because his goals are so heinous.

… We tend to assume the worst of those we’re arguing with; that he’s ignoring this critical point, or that he understands what we’re saying but is being deliberately obtuse. So we end up getting frustrated, saying something nasty, and cutting off any opportunity for real dialogue.

I don’t know that we’re a majority, as Olmsted hopes, but there’s more than just a few of us, at least…

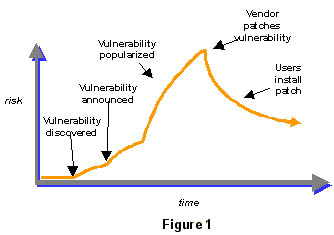

Phase 1 is before the vulnerability is discovered. The vulnerability exists, but no one can exploit it. Phase 2 is after the vulnerability is discovered, but before it is announced. At that point only a few people know about the vulnerability, but no one knows to defend against it. Depending on who knows what, this could either be an enormous risk or no risk at all. During this phase, news about the vulnerability spreads — either slowly, quickly, or not at all — depending on who discovered the vulnerability. Of course, multiple people can make the same discovery at different times, so this can get very complicated.

Phase 1 is before the vulnerability is discovered. The vulnerability exists, but no one can exploit it. Phase 2 is after the vulnerability is discovered, but before it is announced. At that point only a few people know about the vulnerability, but no one knows to defend against it. Depending on who knows what, this could either be an enormous risk or no risk at all. During this phase, news about the vulnerability spreads — either slowly, quickly, or not at all — depending on who discovered the vulnerability. Of course, multiple people can make the same discovery at different times, so this can get very complicated.