Vintage SF Month is hosted by the Little Red Reviewer. The objective: Read and discuss “older than I am” Science Fiction in the month of January.

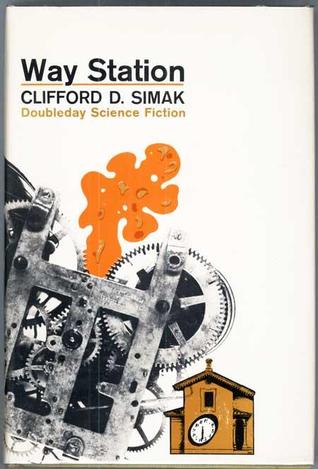

Clifford D. Simak is one of the famous Golden Age authors that I haven’t really caught up with. There’s no time like the present, so I took a spin through his bibliography and settled on the Hugo winning 1963 novel Way Station as my introduction to his work.

Enoch Wallace is an American Civil War veteran who was chosen by the Galactic Federation to maintain a way station for interstellar travel. He looks after the machinery and does his best to greet the alien travelers, even forming some long term friendships among the galactics. Unfortunately, since humanity is not yet ready to join the Galactic Federation, he must keep the station a secret from his fellow humans. He only ages when he leaves the house for his daily walk and thus, even though about a hundred years have passed, he still looks to be about 30 years old. As the novel opens, the US government has discovered Enoch’s longevity and set about monitoring his actions in the small, insular Wisconson town in which he resides. What’s more, they’ve noticed a gravestone with strange markings on his property and when they investigated further, they found an alien body buried there, which they absconded with in order to study.

From a plot perspective, not a whole lot happens for the first half (maybe even more) of the novel. This is the sort of thing that often bothers me, but not here. The character study of Enoch, a simple but open-minded man living a well-worn routine, is livened by the SFnal elements of the story, even if most of those are only lightly addressed. For example, the transportation network that the way station exists on is one of teleportation by duplication, where the original body remains at the source and a copy is created at the destination. We don’t get much information on how this system actually works, nor do we really dive into the philosophical quandaries it presents, which is a fair criticism in some ways, but nothing that an experienced reader of SF could not fill out on their own. A lot of the story’s conjectures raise questions that the novel doesn’t even try to address directly, which I’m sure can be frustrating for some, but worked reasonably well for me (there’s something to be said for SF’s ability to leverage the rest of the genre in order to streamline the current story, and this book does a decent job of that).

When things do start happening in the latter half, what initially felt aimless is revealed to be deliberate and well placed. A large number of potential crises arise in relatively short order, but all of them are extensions of things introduced earlier in the story, often in mundane fashion. Enoch’s ornery neighbors, while normally content to keep their suspicions to themselves, are getting riled up. The Galactic Federation is experiencing an uncharacteristic rise in political strife and there’s a proposal to shut down the transportation path that Earth is on in order to use those resources elsewhere (thus delaying Earth’s potential membership by centuries or even millenia). The US government’s meddling doesn’t help either, as the Federation knows about the stolen alien body and that supports the political factions that think Earth (and this general area of the galaxy) is not worth the trouble. Enoch, having learned alien techniques and maths has done some calculations and determined that Earth, still mired in the Cold War, is headed towards an inevitable nuclear confrontation (he doesn’t use the word Psychohistory, but again, experienced SF readers will be able to put 2 and 2 together). Enoch’s alien friend (who he has named Ulysses) offers Enoch the chance to petition the Galactic Federation for a way to head off war, but the price is high and the political optics would be bad for the transportation network anyway. Finally, the galaxy has some sort of empirically measurable spiritual force that is harnessed by an artifact that has gone missing (along with its caretaker).

The setup is great and quite entertaining. The resolution… may leave something to be desired. Everything is resolved in a pat, simplistic manner. It’s certainly functional, and the book had built up enough goodwill that I don’t really have a major problem with it, but it all just feels a little too convenient. Some of these crises are too easily surmounted. To pick one, non-spoilery example, the government agent that confronts Enoch is shockingly deferential to Enoch’s wishes, and somehow has no problem whatsoever turning the requests around. I mean, I’m sure the bureaucracy in the government has increased since this novel was written, but not by that much. Several other crises are averted by one simple, almost magical event. Again, it’s functional and Simak laid the proper groundwork such that it all fits together in the end (easier said than done, which is perhaps why I’m cutting it slack), but it could be underwhelming. He played the game well enough, I suppose, but I could see it grating others more than it did for me.

Ultimately, though, Enoch is a likable protagonist, in some ways your typical SF competent man, but one who displays a degree of flexibility and open-mindedness that is uncommon. His good natured manner carries the novel even when the plot machinations falter. Simak’s style is simple and doesn’t call attention to itself, but it’s not as stilted or plain as, say, Asimov’s style. In some ways, this is an unusual novel of contraditions. Galactic scale space opera tropes portrayed via the simple, pastoral setting of a shack in small-town America. Big ideas and responsibilities laid at the feet of a small man. And yet it works. Indeed, it probably works because of the contradictions. I’m positive that this novel would drive some folks nuts, but I had a really good time with it and shall endeavor to read more Simak. Someday. Way Station actually won the Hugo Award in 1964 against some strong competition, including Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle, Heinlein’s Glory Road, the serialized version of Dune (which would go on to win when published in book form), and Andre Norton’s Witch World. Of those, I’ve only actually read Dune, but it certainly seems like both Cat’s Cradle and Glory Road cast a bigger shadow than Way Station, which seems like the most conventional SF choice (but then, the Hugo is a populist award, so perhaps the conventional choice wins out over fantasy, post-apocalypse, or however you’d describe Dune).